New hire needed? No problem, let’s find the market median for the role.

Startups often approach compensation as a series of one-off exercises, benchmarking each role individually against market data as needs arise.

It feels solid. You're paying "market rates," after all.

But compensation expert Matt McFarlane argues there's a fundamental flaw in this approach.

For him, the best compensation strategies are 'market-informed'. Market data becomes one input in a bigger equation that factors in the specific context of your unique company.

It’s about moving from "what does everyone else pay?" to "what should we pay given our context, goals, and constraints?" or from “we want to pay our people generously” to “what payroll can we actually sustain?”

First things first, what do we mean by ‘market-driven’ and ‘market-informed’?

With a market-driven approach the company relies solely on benchmarking data to make pay decisions.

A target percentile is chosen, you use benchmarking data to look up what the market pays for a role at that percentile, and that's the answer for the salary your employee will receive. This approach is sometimes called 'spot salaries' or 'market pricing' – using the market reference point as the salary.

“Market-driven takes the benchmark as gospel” explains Matt McFarlane, Director at FNDN.

“Most commonly, startups will align with the 50th percentile simply because it feels competitive whilst comfortable – with no deeper ‘why’ behind that decision and how it fits into the company’s wider context.”

Market-informed compensation uses that same data as an input to a compensation structure that’s also informed by the company’s business model, strategic priorities, financial runway, company culture, employee feedback, career progression pathways, and more.

“The company’s philosophy on compensation and their financial position are equally important inputs as the market data, but I see so many startups skip that step and head straight to the data,” says Matt. “The most effective approach is a marriage between market data and company context.”

How does this actually play out in practice?

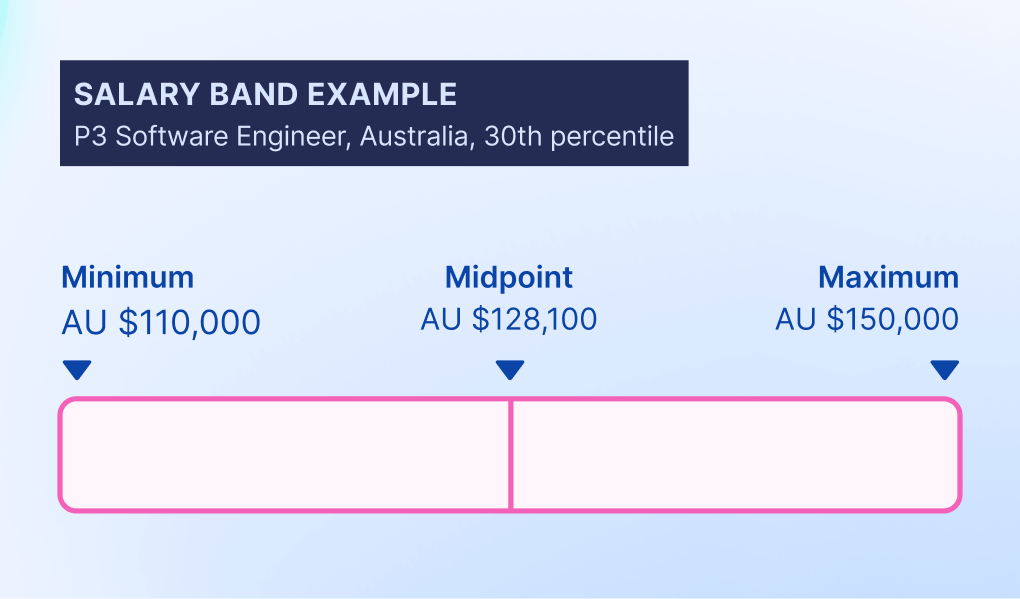

Let's take an example. Say you're hiring a mid-level (P3) software engineer in Australia, and you target that comfortable 50th percentile market alignment.

Market-driven approach: You price this role individually using a compensation benchmarking tool like Ravio, market data shows the 50th percentile is AU $138,900 (as of July 2025) – so that’s the salary the chosen candidate will be offered.

Market-informed approach: You've already built salary bands for all roles, levels, and locations based on your company context.

Maybe your P3 software engineering band for Australia runs AU $110k-150k (with the midpoint at the 30th percentile of AU $128,100) because you're a seed-stage startup with limited cash, but able to offer competitive equity and growth opportunities – so you're 'lagging' the market, rather than 'leading' it, but with clear rationale.

When hiring, you place this person appropriately within your existing band based on their experience and skills – perhaps AU $120k for someone newer to the level, or AU $140k for someone with strong expertise who won’t take long to be promoted up to the next level.

What are the risks of being too market-driven with compensation?

On paper, market-driven compensation sounds objective, defensible, systematic.

In practice, Matt sees companies run into the same problems again and again by not building the company’s context into pay decision-making processes.

Unsustainable payroll costs that ignore business reality

Companies that pick a target percentile at random and then blindly follow market rates often end up overspending on payroll.

That means no compensation budget left for future compensation reviews, promotions, or maintaining market-competitiveness as you grow – or worse still, unsustainable costs might force headcount cuts later down the line.

Matt shared an example of working with the team at Oyster HR early on in the company’s journey.

As a SaaS startup, they had initially aligned new hire salaries with market data on average rates at other SaaS companies – which tend to be relatively high, because the profit margins in SaaS mean it’s easier for startups to start generating revenue and have budget to play with.

But in reality, Oyster actually operated largely as a service business in the early days, providing consultative support to global teams on the logistics of distributed workforces.

“The reality of the business was different to that of the market data,” Matt highlights, “which could easily have led to the company overextending itself on payroll costs.”

Inconsistent career progression

“Benchmarking data gives you the aggregated market rate at each job level – but there often won’t be a neatly linear progression between each job level,” Matt explains.

“The differential between a P2 and P3 level might be substantially different to that between a P3 and P4 level, which means if you simply pay each employee at the market rate, you can end up with an inconsistent career ladder from a compensation perspective.”

Let’s take that same 50th percentile Australian Software Engineer from our earlier example, for instance.

We can see from Ravio’s salary benchmarking data that there’s a 28% increase in the median salary between P2 (AU $108,100) and P3 (AU $138,900), but a 24% increase between P3 and P4 (AU $172,000). Not a huge difference, but something that could create inconsistencies and perceptions of unfairness once you apply across all job levels and roles in an organisation without a structured approach to pay progression.

This is exacerbated if you rely on traditional salary surveys by providers like Radford or Mercer.

The manual nature of the data collection is prone to differing interpretation by different companies submitting their survey responses, which leads to a whole jumble of different job roles and levels in the resulting data.

It’s common, for instance, to see a role where a level has a lower average salary than the level below it (or vice versa) – if you follow that for your own salary decisions, it’s easy to see how inconsistencies and unpredictable career paths arise.

Employee-to-employee inequities grow unchecked

When compensation decisions are made on a case-by-case basis, the company-wide view of compensation isn’t considered – especially true when there’s no centralised owner of the Rewards strategy, with line managers making ad hoc decisions for their team.

Inconsistencies aren’t caught, and there’s no mechanism to compare across roles and ensure a Senior Product Marketing Manager and Senior Product Manager with similar scope and impact are paid fairly relative to each other.

Increasing pay transparency regulations (from the ban on pay secrecy in Australia to the EU Pay Transparency Directive in Europe) make this especially problematic.

Matt highlights that these inconsistencies can even exist for two employees in exactly the same role and level.

“Often the latest market data is used to make one-off decisions on new hire salaries, without even checking what existing employees in that role are being paid,” Matt explains. “If the market has shifted, you end up with salary inversion, with new hires paid at new market rates while existing experienced employees stay aligned to outdated data.”

If the company hasn’t considered how it will ensure all employees stay market-aligned or how pay progression should work for the team, it can create what Matt calls “cowboy hires” – situations where market timing or a candidate’s salary negotiation skills matter more than company loyalty or job performance for determining how an employee is paid.

“When long-term employees watch new joiners earn more for the same work,” Matt says, “it inevitably erodes trust and drives turnover amongst your most valuable people.”

How to implement a market-informed approach

The shift from market-driven to market-informed compensation means building market data into a structured framework that’s tailored to match your company’s context.

“There’s the bottom-up ‘what does the market pay’ approach, and then there’s the top-down ‘we believe in generous pay for our team’ philosophy,” Matt says. “The best solution is going to be somewhere in the middle – it’s all about finding the right compromise.”

So how do you get there in practice?

For Matt, the two key building blocks of a market-informed approach to compensation are a compensation philosophy that articulates the company context, and a salary band structure that turns that into a decision-making framework.

Compensation philosophy is your starting point

When your company has been reliant on a market-driven approach, aligning employee salary with the market reference point for their role, Matt advises also taking “an audit mindset”.

“The aim of the audit is to understand what problems your current approach is creating, so that you can build the right solution,” Matt explains.

The audit should always include reviewing:

- Candidate expectations – talk to the Talent Acquisition team and find out typical offer acceptance rates by role and level, as well as how often they’re getting feedback from lost candidates that the offer is not competitive.

- Turnover data – find out how your retention rates compare to your talent competitors, and how often compensation is being cited as a reason that people move on.

- Salary compression data – aggregate all your internal salary data and find out how often new hires are being paid more than experienced employees in the same roles.

- Benefits expenditure and usage – find out which employee benefits are actually being used, and which are a waste of budget.

- Employee feedback – understand how much clarity do employees have on how their compensation package is decided, and what their career (and pay) progression could look like within the company.

This information should then be used to inform stakeholder conversations on how compensation fits with your company's business priorities, values, culture, and financial runway.

“Your role is to ensure clarity on the problem and the goals for compensation, and then create a solution that helps to achieve those goals,” says Matt.

"I always spend a lot of time deeply understanding the mission, the culture, the kinds of people that are going to help deliver on it, and the current situation from a financial perspective," says Matt.

“You want your compensation decisions to be strategic – these are the calibre of people we need to hire to hit key milestones based on our business model, it will cost us this, and it will have this impact on our P&L.”

Matt’s advice is to sit down with your key stakeholders and have an open conversation that includes questioning assumptions on pay, like:

- Should two people in the same role ever be paid differently?

- Should loyalty be rewarded?

- Should business impact be rewarded?

- Which total reward levers best align with our culture and team needs?

- Who do we compete with for talent?

- How secure is our financial runway?

The aim is to reach consensus on a set of core principles that define how the company will compensate its people.

That includes, but isn’t limited to, how market competitive you truly want to be – which might end up differing for different roles, in tech, for instance, it’s common for software engineering teams to be paid at a higher target percentile.

“One great example I’ve seen is Athyna,” shares Matt. “For their founder, Bill Kerr, changing the financial futures of his team is a big motivator, which means that equity has been an important compensation lever – and to reflect that they’ve offered RSUs from the very beginning to ensure employees have full ownership of their equity with no caveats.”

“You want your compensation decisions to be strategic – these are the calibre of people we need to hire to hit key milestones, it will cost us this, and it will have this impact on our P&L."

Director at FNDN

💡Don’t automatically default to the 50th percentile

“25th percentile isn’t a dirty word,” says Matt. “It’s perfectly okay to pay below market median if you’re being strategic about it.”

It might be that you’re an early-stage startup and you simply don’t have the budget to offer higher salaries.

But it’s also common for companies to under-index on salaries but offer highly competitive equity compensation, impressive flexible working opportunities, or strong career mobility – all of which might be more important than base salary for the employee base you’re trying to attract and retain.

As long as you aren’t contravening minimum wage laws and you can explain the rationale behind compensation decisions to your team, the decision is yours.

Build structured salary bands based on those philosophical principles

"The end-goal is to build coherent salary band structures, instead of treating each role as an isolated data point," Matt explains.

So what does that actually look like?

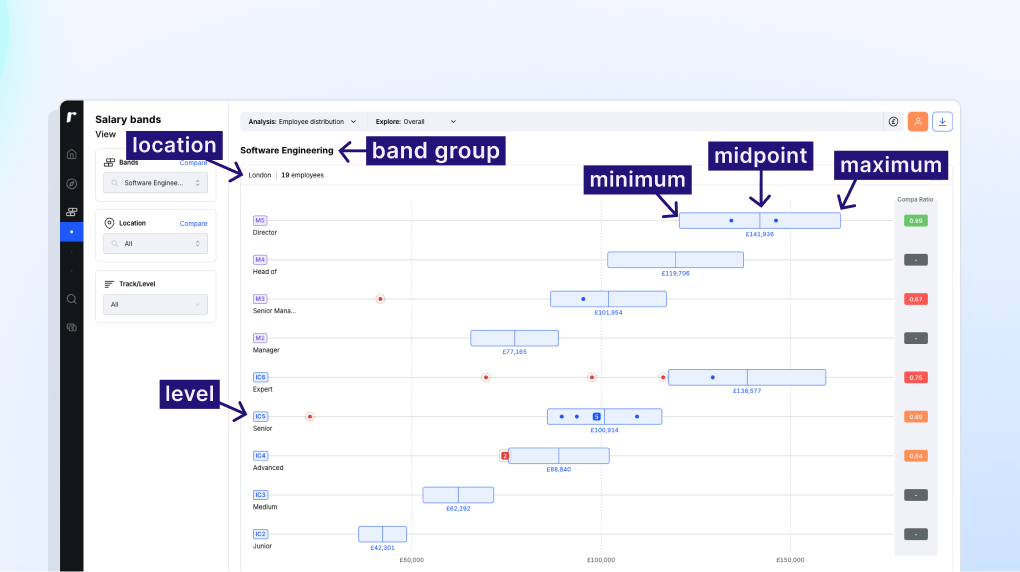

Salary bands translate the compensation philosophy into a structure for making company context-informed, market-informed, and internal pay equity-informed compensation decisions – with the core components being:

- Band grouping: Each band represents employees who should be paid equitably – typically those in the same role, at the same level, in the same location.

- Band midpoint: The middle of each band reflects the market rate at your chosen target percentile (and needs to be refreshed regularly to ensure you stay in-line with the market). Crucially, that percentile choice now comes from your defined compensation philosophy – informed by your company stage, financial situation, and how competitive you want base salary to be versus other total rewards elements.

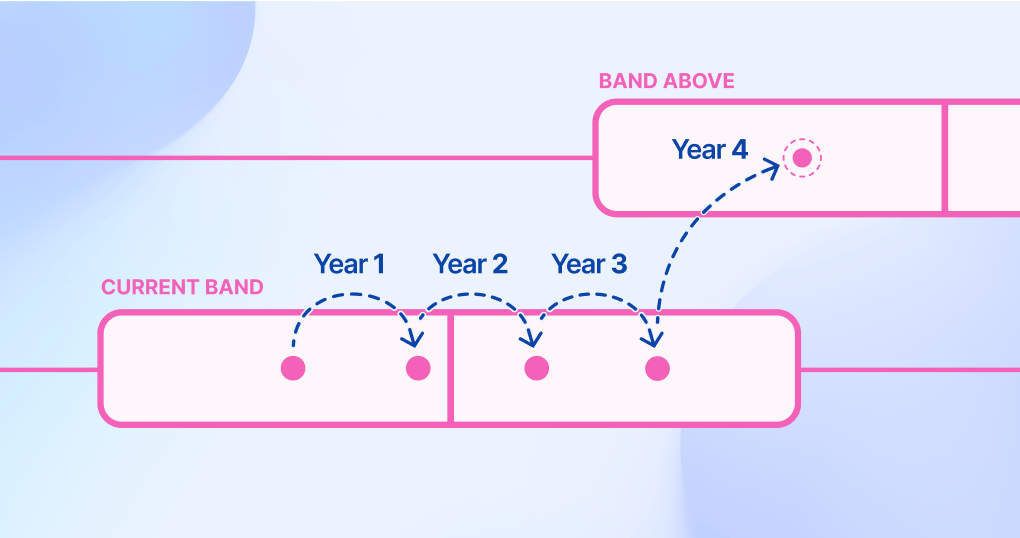

- Band range (minimum to maximum): This range reflects where an employee sits within the scope and responsibilities of the job level that their band aligns with. When hiring, you place someone in the band position that aligns with their experience, skills, impact, and autonomy at that level. For existing employees, the range enables pay progression (and prevents pay inversion) – as their capabilities grow within the role, their position-in-band should move up and their pay increase accordingly. Typically 15-20% either side of midpoint provides meaningful enough differentiation across the job level.

“Once you have the structure in place, make sure to also review the differential between each band and make adjustments to ensure fair promotion increases between each job level,” Matt advises.

“You want to smooth out any of those inconsistencies in the data to create a relatively linear progression with no huge jumps or tiny bumps when someone moves up a level.”

💡Use a salary band tool to create, visualise, and maintain the structure

Software like Ravio’s can make building and managing this structure much easier.

Rather than wrestling with complex spreadsheets, you can automatically create salary bands based on reliable, relevant, real-time market data, and tailored to your organisation’s compensation principles.

Having your salary bands in Ravio makes it simple to refresh your bands against the latest market data, identify pay equity issues, and share transparently with managers and employees – while maintaining control over what information is visible to whom.

Let's revisit our Australian software engineer from earlier as an example.

Based on your compensation philosophy, you've decided to target the 30th percentile for base salary (because you're pre-revenue and offer competitive equity to offset lower salaries), and you’ve chosen a band width of +/- 15% around the midpoint to allow for standard career progression.

Here's how your P2-P4 band structure might look:

- P2 Software Engineer: AU $84,200-AU $113,900 (midpoint AU $99,000 at 30th percentile)

- P3 Software Engineer: AU $108,900-AU $147,300 (midpoint AU $128,100 at 30th percentile)

- P4 Software Engineer: AU $135,200-AU $183,000 (midpoint AU $159,100 at 30th percentile)

Hire a P3 with limited experience at that level? They might start at AU $115,000 – lower pay than their colleagues at the same level with more experience and higher impact.

But, if they perform well, they might average a 5% salary increase over the next three years as they grow into the role (moving from AU $115,000 to AU $118,450 in year 1 to AU $122,003 in year 2 to AU $125,663 in year 3) – and receive a promotion after 4 years with the company that brings them into the lower end of the P4 job level and band.

This structure ensures strategic decisions (30th percentile reflects your compensation philosophy), market alignment (the band midpoint and range informed by benchmarking data), fairness (all P3s are in the same band), and progression opportunity (meaningful increases within level).

About FNDN

Matt McFarlane is Director at FNDN, where he helps scaling technology companies build compensation practices that are clear, fair and competitive.

As one of our trusted partners, FNDN clients are also able to get discounted access to Ravio’s real-time benchmarking data and compensation tools.