Equity compensation is typically the most complex element of total rewards to navigate.

From deciding who should get startup equity (and how much), to what type of equity compensation to offer, to the balance of cash vs equity in an employee’s compensation package, and much more.

There are a lot of decisions to make when deciding how to structure equity compensation.

Plus, there are also a lot of complicated tax rules to decipher too – especially for companies with employees in multiple locations with different laws.

To help, we’ve put together this guide to startup equity compensation.

It contains a step-by-step exploration of how to structure an equity compensation package for startup employees, as well as an inside look at Ravio’s data on typical startup equity plans – plus we’ve covered all the FAQs on startup equity too.

What is equity based compensation?

Equity compensation is a form of non-cash pay that grants employees an ownership stake in the company they work for, in return for their work and contributions.

The central premise is that the company should become more valuable over time, as it grows and scales in revenue, which means that the equity becomes more valuable too.

Employees have the option to sell their shares at various points in the company’s journey, at which point the equity turns into cash payment.

Should your startup offer employees equity compensation?

Equity compensation is particularly common for startup companies to offer employees, as part of their total rewards package.

This is because earlier stage startups are typically unable to compete on cash salaries for top talent – larger, more established companies with higher profits are always likely to offer employees a higher base salary.

It’s easier for startups to compete on equity for talent acquisition and retention, because there’s no additional payroll cost in the short-term.

For startup employees, joining early in a company’s life and gaining startup equity means that if the company is successful that equity will significantly increase in value over the employee’s tenure, which could mean a big cash payout in the future.

However, there are pros and cons to offering equity compensation, both for employer and employee. Let’s take a look.

Equity compensation: the pros

The advantages of offering equity compensation to employees centre around the ability to compete when hiring top talent and retain that talent for the long-term, whilst keeping payroll costs down.

Here’s the key reasons that companies choose to offer equity compensation:

- Attract talent with competitive compensation. Equity compensation gives employees an ownership stake, meaning that there’s an opportunity for a large payout in the future if the company is successful and increases its valuation. Many startup employees are keen to maximise equity compensation for this reason, so it’s a great way to ensure a competitive compensation package.

- Lower tax rates. In the long-term, if equity options are sold for cash then the financial gains are typically taxed at lower rates than salary income (especially in countries with tax-advantaged employee equity schemes like Enterprise Management Incentives (EMIs) in the UK or bons de souscriptions de parts de créateurs (BSPCE) in France. This makes it an even more attractive option for many employees.

- Manage payroll costs. For employers, offering equity compensation to employees can be an effective way to keep payroll costs lower – attracting talent without having to offer a high base salary. It’s common for equity to accompany a lower-than-average salary offer.

- Incentivise employees to contribute to company success. When employees have equity compensation, their financial reward is directly tied to the future success of the business – which can be a great motivator.

- Retain talent with vesting schedules. Equity compensation always comes with a vesting schedule which determines when the equity will be transferred into the full ownership of the employee. This provides an in-built retention mechanism, as employees are more likely to stay with the company for the duration of the vesting period to ensure their equity stake is fully unlocked. Plus, equity refresh grants make it possible to continue this retention mechanism by granting additional equity with an additional vesting period.

- Profit sharing. Equity compensation gives employees an ownership stake, which enables founders and leaders to give back and share the financial success of the business with the employees who helped to build it.

Equity compensation: the cons

Whilst many companies choose to offer equity compensation to employees for the reasons outlined above, there are some downsides.

For employees, the main risks are:

- If the company fails, the financial gain will never be realised. The biggest risk with equity compensation is that it only becomes worth something if the company is successful. If this doesn’t happen, then the equity is worthless. This is especially risky if an employee is accepting a lower salary offer in the hope of longer-term financial gain from their equity.

- Limited liquidity. Even if the company is successful and the employee’s equity increases in value, there are only certain times when an employee can convert their equity stake into cash. The exact terms of this depend on how a company’s equity compensation plan is structured, but typically the employee can only be exercised (sold for cash) when particular liquidity events take place e.g. an IPO or merger/acquisition.

- Golden handcuffs. When there's a financial incentive to stick with a company, it can lead employees to feel obliged to do so, even if it isn't a great fit. This is why Netflix opted to go against the standard FAANG approach to not offer equity by default and to grant stock options fully vested – for Netflix employees it's purely a financial risk decision, not an incentive for retention.

Because of this complexity, some job candidates will always favour cash compensation over equity, so if you’re trying to balance a lower salary offer with equity compensation, you may lose some candidates along the way.

And for company founders and leaders there are risks to releasing startup equity to employees too:

- Lose top talent to higher salary offers. Because of the complexities outlined above, some job candidates will always favour cash compensation over equity. So if you’re trying to balance a lower salary offer with equity compensation, you may lose some great candidates along the way.

- Diluted control. Granting equity to employees dilutes founder control of the company, because a slice of the ownership is handed over to employees. This is known as dilution, and is a major consideration for many founders.

- Legal and tax implications. Every company has specific laws, reporting requirements, and company taxation policies when it comes to managing company equity and granting equity to employees. Managing an equity compensation plan means understanding and complying with those laws, which can be very complex, especially if granting equity to employees across several different countries. Time, effort, and legal and financial counsel will be needed.

- Conflicting advice. There are lots of ways to structure an equity compensation offering, and it’s difficult to decide which is right for your company. As a founder, when you’re considering whether to offer equity compensation to employees and how to do it, you’ll come across lots of conflicting advice and examples or how other startups approach equity – without much evidence or objectivity. It’s very difficult to cut through that noise and decide what the right framework is for your equity compensation offering, which can be off putting.

Subscribe to our newsletter for monthly insights from Ravio's compensation dataset and network of Rewards experts 📩

How to build an equity compensation package: a step-by-step guide

Once you’ve decided you’re going to offer equity to employees, how do you actually go about building an equity compensation package?

There are lots of different elements to consider and decisions to make/

Here’s the key steps in brief:

- Step 1: Consider cash vs equity – how will equity compensation fit into the total compensation package?

- Step 2: Decide which employees will receive equity compensation

- Step 3: Decide how much equity to allocate to the employee option pool

- Step 4: Decide which type of equity compensation to use

- Step 5: Choose the vesting schedule

- Step 6: Use equity benchmarks to calculate new hire equity grants

- Step 7: Build equity compensation bands

- Step 8: Decide whether equity refresh grants will be included in ongoing compensation reviews

- Step 9: Create clear documentation and guidance for employees on equity compensation.

Let’s take a closer look at each of these steps.

Step 1: Consider cash vs equity – how will equity compensation fit into the total compensation package?

Different companies use equity compensation in different ways.

For some cash-poor companies (especially early-stage startups), equity compensation offers a way to compete for talent without overextending on payroll costs. In this case, the total compensation package will be heavily weighted to equity – a high equity to salary ratio.

For other companies, equity compensation might be part of a market-leading compensation philosophy which aims to attract the best talent through offering very competitive compensation packages. In this case, there will be a balance of base salary, equity, employee benefits, and variable compensation.

When it comes to building an equity compensation package, starting with those core compensation philosophy principles is key – how does your company think about rewarding employees, and where does equity fit into that? This will help to determine the balance between cash and equity in terms of total compensation.

Step 2: Decide how to distribute equity – which employees will receive equity compensation

Some companies choose to offer equity compensation to all employees, as default.

Other companies use equity compensation as an optional element, granted only to certain employees.

As we saw earlier in this article, equity compensation can be valuable for attracting and retaining talent, which might make you lean towards offering equity to all employees.

But, at the same time, the more employees have equity, the more diluted ownership of the company becomes, which can be a downside for founders.

There’s no right or wrong answer, it simply depends on the company’s goals, priorities, values, and compensation philosophy.

For companies that opt only to offer equity compensation to some employees, common approaches include:

- First employees and early hires. It’s common for the first few employees to join a company (after founders) to be granted equity. This reflects the risk they’re taking in joining such an early-stage startup, as well as the fact that there’s likely a much lower salary offer on the table – sometimes these early hires will even be equity only initially.

💡 Expert insight: Should the first employees receive a set percentage of equity?

For Ravio co-founder Merten Wulfert, it’s common to see first hires offered startup equity in “quite an arbitrary way” – for instance, 1% ownership granted to the first three hires.

“This is a bad idea,” says Merten, “because there’s no logic applied, which means inconsistencies and inequities will be there from the very start.”

Instead, “employee equity at the start of a startup’s journey should reflect the level of risk the employee is taking on by joining a company in the very early days”.

For example, a first-time founder with very little external funding and unproven business model and no customers will most likely have to give up much more equity to early hires than a successful serial entrepreneur who has secured a high amount of external funding from reputable investors and is already seeing traction.

Merten recommends using the following factors as a framework:

- How much traction does the company have?

- What is the potential upside value of the equity for them?

- What salary are you able to offer?

- What is the candidate giving up by leaving their current role (including any equity left on the table due to vesting)?

- Leadership team. It’s common for equity compensation to be a major point of negotiation for leaders joining a startup. Depending on the company stage, they’re likely taking a salary cut to join a startup which they see as having future potential, so an equity stake is an important driver for them in joining the team to ensure they benefit from helping the company realise its potential.

- Equity for some departments or levels of seniority. Just like with salaries, competitive equity compensation varies depending on the job role and level of seniority (which is why it’s vital to use an equity benchmarking tool like Ravio when building an equity compensation package). It’s therefore common for companies to offer equity only to certain job levels or job roles in order to win top talent over – or to offer those roles more equity than others. In the tech industry, it’s typical for product and engineering teams to receive higher equity, for instance, than commercial teams.

Step 3: Decide how much equity to allocate to the employee option pool

Equity is essentially company ownership, so when equity compensation is granted to employees it means that founders are giving away a portion of company ownership.

For this reason, deciding how much equity to allocate to employee compensation is an important decision to make.

The key is to create a balance between not giving away too much control, whilst ensuring that the equity compensation offered to employees does represent a meaningful stake in the company.

Most founders first take a top down approach to determine what overall percentage of equity can be allocated and set aside for employees – known as the employee option pool.

It’s typical for founders to allocate between 5-15% of equity to employees in the early stages of a company (seed to series A funding).

However, we’d recommend taking a bottom-up approach.

This means building a hiring plan that models out the employees you plan to hire in the foreseeable future by role and seniority.

Then design a simple framework to determine how much equity compensation you plan to offer per employee (both new hire and equity refresh grants if applicable) and how this will differ for different departments, seniority levels, or any other distinctions you plan to make.

From there you’ll be able to calculate how much equity overall you’ll need to fulfil equity compensation plans over the foreseeable future – and this is the amount of equity you need to set aside in the employee options pool.

Repeat this exercise ahead of each new funding round, or whenever the company goes through a significant strategic shift.

Step 4: Evaluate the different types of equity compensation – RSUs vs VSOPs vs stock options

The overall equity compensation plan is typically called an Employee Stock Ownership Plan (ESOP).

However, there are many different vehicles for granting equity to employees – all with different pros and cons depending on your company’s priorities.

The most commonly used options are:

- Stock options

- Virtual Stock Options (VSOPs)

- Restricted Stock Units (RSUs)

How do stock options work for employee equity?

Stock options give an employee the right to buy company shares at a fixed price in the future (the strike price – sometimes also known as the exercise or grant price)

If the company is successful its stock will increase in value over time and the employee can therefore make profit by buying shares at the fixed strike price, and selling on for the actual market price of the shares – pocketing the difference.

Tax implications are important to consider when deciding on how to grant employee equity.

Each country typically has its own taxation requirement, so they can become quite complex to administer.

For instance, in the UK the following taxation applies to non-qualified stock options:

- Employer pays national insurance tax when the employee exercises i.e. buys the shares

- Employee pay income tax when they exercise the shares, on the difference between the strike price and the actual market value

- Employees pay capital gains tax when they sell the shares, on the difference between the market value at exercise and the market value at sale.

However, it’s also common for countries to have tax favourable stock options schemes – and, for this reason, these tend to be the most popular way to offer equity compensation to employees.

For instance, in the UK, the Enterprise Management Incentive (EMI) scheme is tax favourable both for employers and employees:

- The employer is not taxed at all, and may even eligible for corporation tax deductions by using the scheme

- The employee is not taxed at exercise, and whilst capital gains tax still applies at the point of sale, they may qualify for reduced rates under Business Asset Disposal Relief (BADR).

EMIs aren’t an option for all UK employers, though, as only companies with under 250 employees are eligible for the scheme.

Other examples in the European market include Bon de Souscription de Parts de Créateur d'Entreprise (BSPCE) in France, and the Key Employee Engagement Programme (KEEP) in Ireland.

How do VSOPs work for employee equity?

A Virtual Stock Option Plan (VSOP) enables an employer to grant ‘virtual’ shares (also known as phantom shares) to an employee as well as a nominal strike price.

There’s still a vesting schedule, as with real shares, but instead of having actual shares and an ownership stake in the company, at the point of a liquidity event (typically an IPO) the virtual shares are converted into a cash benefit. The employee is paid a cash equivalent to the market value of their virtual shares, minus the nominal strike price.

As with stock options, there are taxation requirements which apply for both employer and employee when the virtual shares are ‘sold’ i.e. converted into a cash benefit. In the UK, for instance, the employer will pay national insurance tax and the employee will pay both income tax and national insurance on the cash benefit.

How do RSUs work for employee equity?

Restricted Stock Units (RSUs) grant employees actual shares of the company’s stock – unlike stock options (the right to buy shares later) or VSOPs (virtual shares).

However, RSUs are ‘restricted’ because the stock is not actually owned by the employee until it has vested.

Vesting occurs over a designated period of time (the vesting schedule or period), with the stock ‘restricted’ until that vesting period has elapsed.

With RSUs there is no strike price, instead the employee simply makes money by selling the shares they have been granted – especially if the company’s shares increase in value between the time they vest and the time they are sold.

Taxation requirements apply at the point that the shares vest and/or are sold (rather than at exercise, as with stock options). In the UK, for instance, the following taxation applies to RSUs:

- Employer pays national insurance tax when the employee’s shares vest

- Employees pay income tax on the ‘fair market value’ of the shares when they vest

- Employees pay capital gains tax when they sell the shares, on the difference between the market value at vest and the market value at sale.

Like with stock options, some countries have tax favourable schemes available for RSUs. For example, in the UK both Share Incentive Plans (SIPs) and Save As You Earn (SAYE) are schemes which offer tax favourable conditions for both employer and employee – but in both cases may require the employee to put in money upfront to pay for the shares, which can make them a less attractive option.

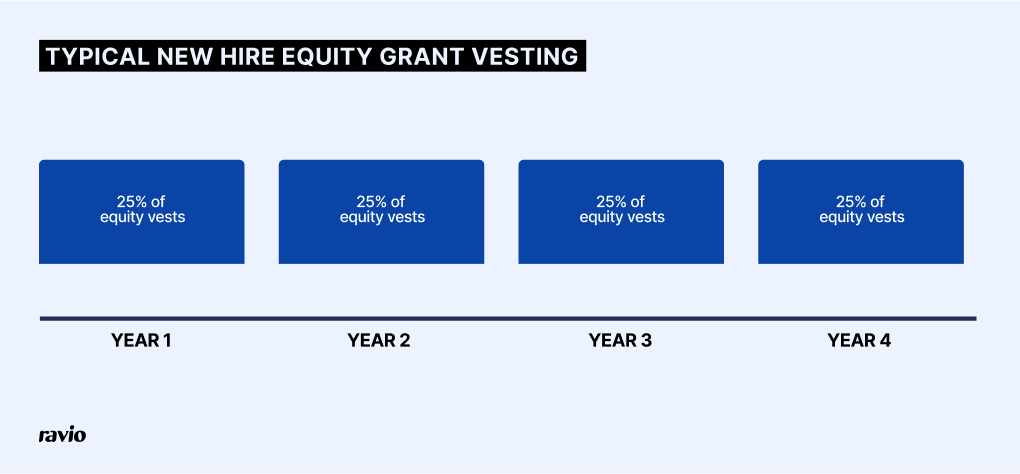

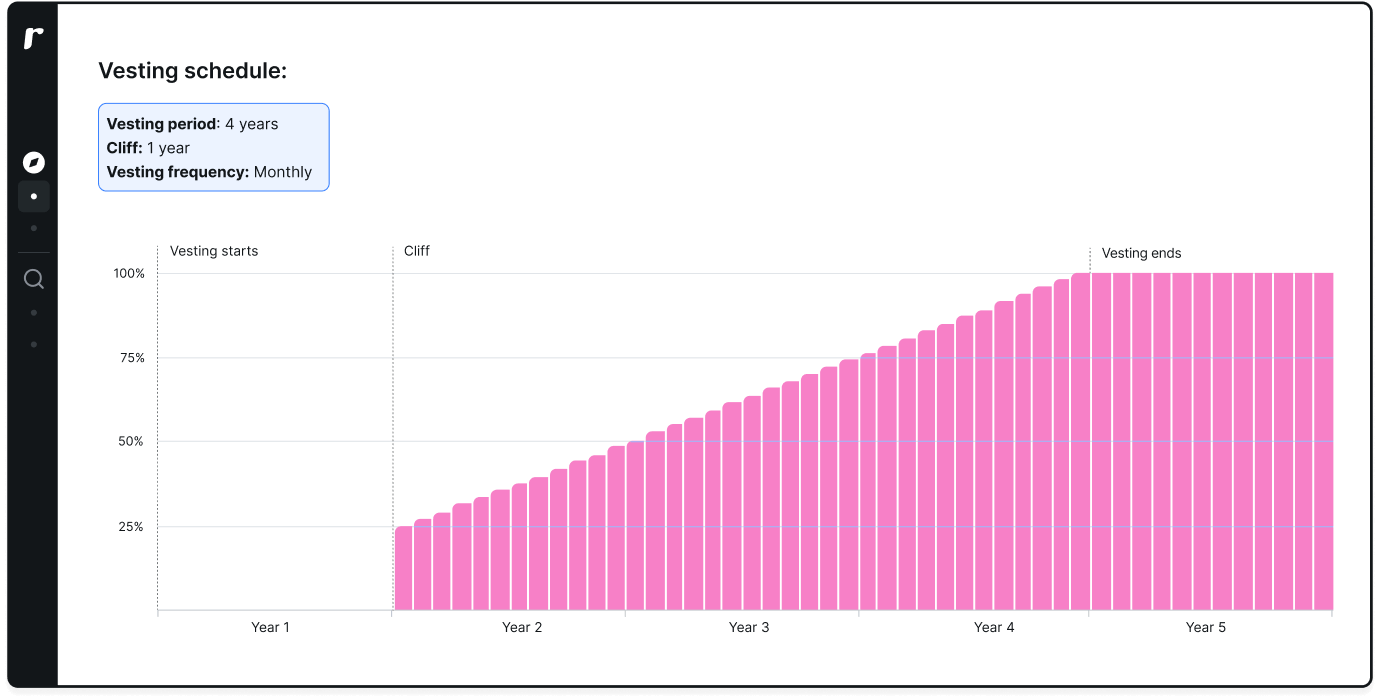

Step 5: Choose the vesting schedule

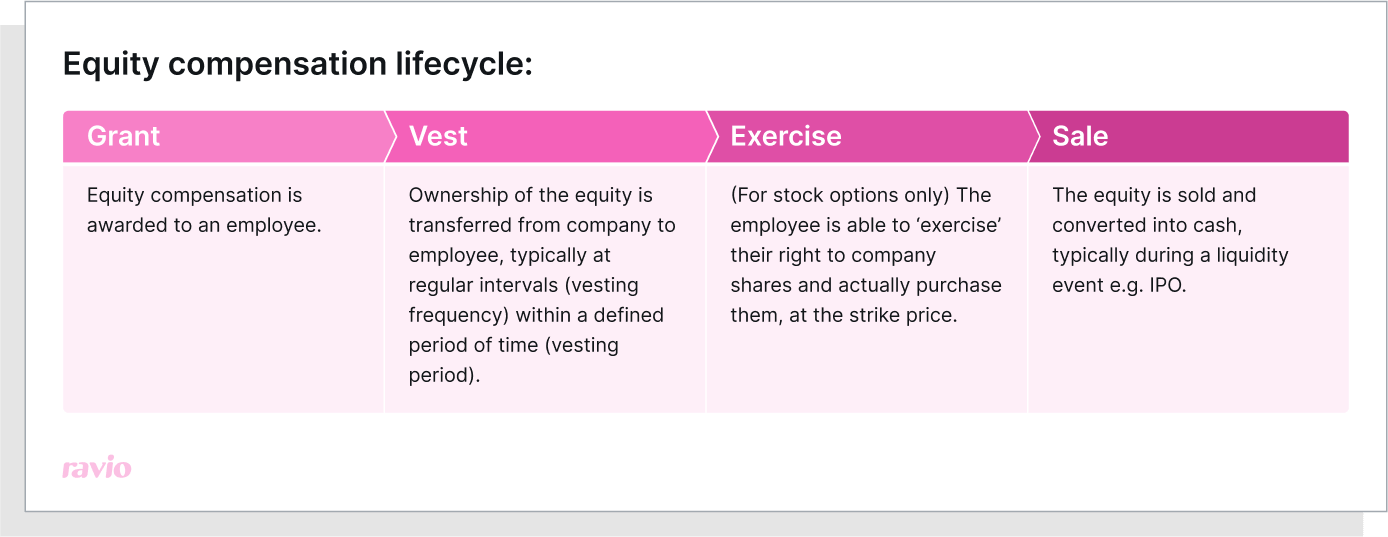

In equity compensation, vesting is the legal process of transferring ownership of shares from company to the employee.

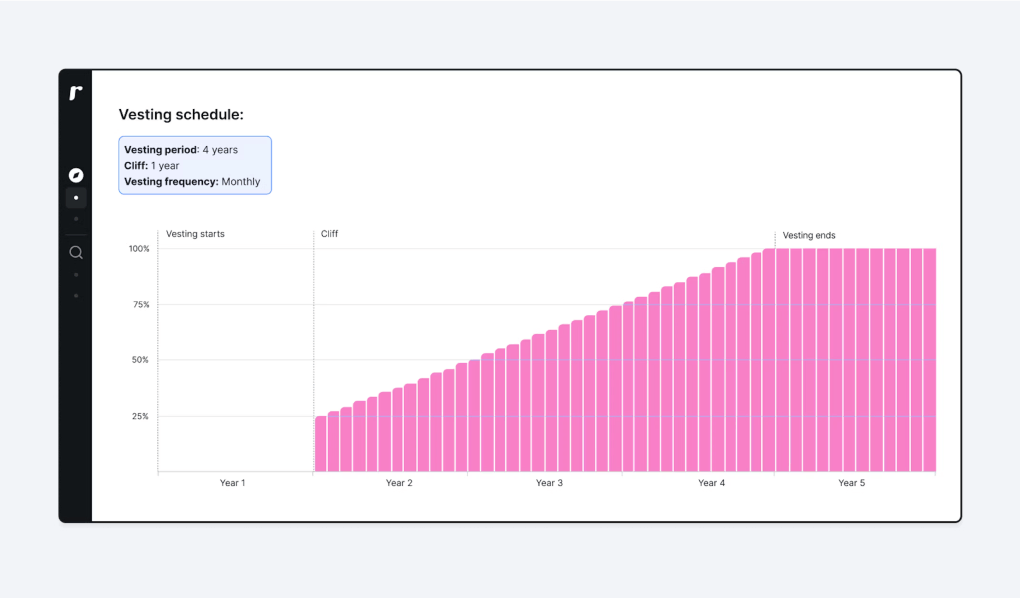

Companies usually set a vesting schedule (or vesting period) that takes place gradually over a pre-determined period of time. Within the vesting schedule equity will vest at regular intervals (the vesting frequency) – typically monthly, quarterly, or annually.

There’s also typically a set cliff within the vesting schedule, a period of time which must pass before the shares start to vest. This gives a buffer for companies to ensure that the employee is a good fit and contributes to the company before they actually gain equity.

The vesting schedule, vesting frequency, and cliff enables companies to give employees an incentive to stick with the company – if they stay until the end of the vesting period, they’ll be able to receive the full financial upside of their equity compensation.

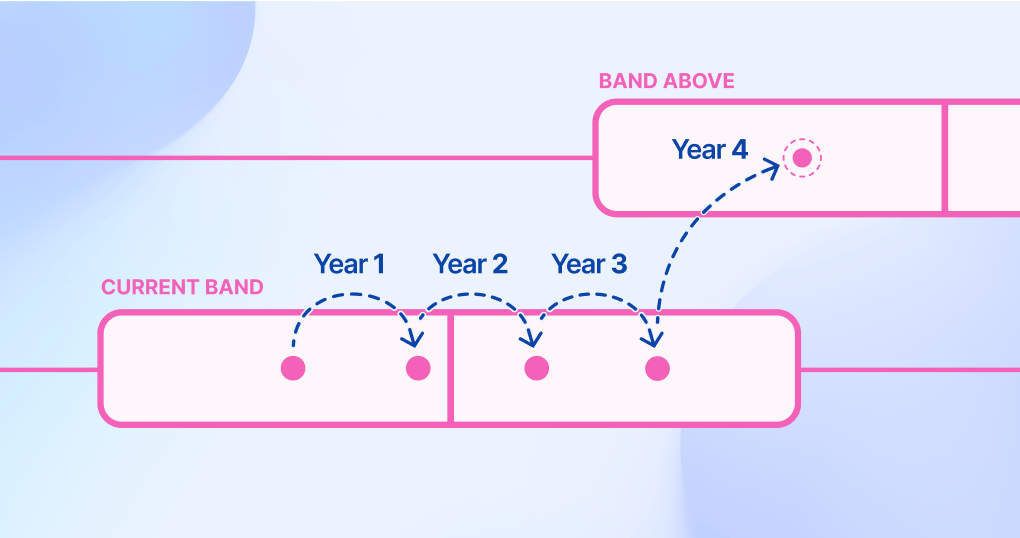

This can be a strong employee retention mechanism, especially if coupled with equity refresh grants which provide additional equity compensation with a new vesting schedule.

However, a short vesting schedule will also be attractive for employees too as they are able to receive the full financial benefits of their equity compensation more quickly. A more frequent vesting schedule is also more attractive for employees, meaning that they’re less likely to leave equity on the table if they do end up leaving the company before the end of the vesting period.

The most commonly cited vesting approach is a 4 year vesting period with monthly vesting and a one year cliff.

However, it’s also become a trend amongst FAANG companies in tech to switch to a much shorter vesting period to increase compensation competitiveness. Doordash, for instance, have removed their cliff entirely so that vesting starts from day one, and several companies including Coinbase, Lyft, and Stripe have switched to a one year vesting period.

Later in this article we’ll explore Ravio’s data to see whether this is accurate.

Step 6: Decide the exercise window

If you opt to grant equity as either stock options or VSOPs, then you’ll also need to define an exercise window, i.e. the time period in which the options can be turned into real shares in the company.

Because stock options and VSOPS represent the right to buy shares in the future, rather than actual company shares, they are typically granted with an expiration date, after which this right can no longer be exercised and so the equity becomes worthless for the employee.

The market standard exercise window tends to be 10 years – but there is, of course, variance on this from company to company.

The key considerations here are:

- A short exercise window can be seen as unfair for employees, as it’s less likely they’ll actually be able to make financial gain from the equity compensation – and this could impact hiring and retention objectives.

- A long exercise window has risks for the company, especially if the company is subject to any reporting or withholding tax obligations.

💡 What about the post-termination exercise window?

The post-termination exercise window defines the period of time in which employees are able to exercise their right to buy shares, after leaving the company.

There are regulatory requirements on post-termination exercise windows for some equity vehicles. For instance, if UK employees are granted EMI share options then there is a legal requirement that they must exercise within 90 days of leaving employment to avoid losing the tax benefits of the scheme.

Outside of this, companies are able to set their own post-termination exercise window.

Historically in the tech startup scene it has been common for companies to require employees to exercise their options within 90 days of employment ending, regardless of any regulatory requirements.

However, this can be seen as pretty unfair, penalising departing employees who are faced with a choice between:

- Not exercising their options and leaving the potential cash value of their equity compensation on the table

- Exercising their options, meaning they pay the upfront costs of exercising and the tax required at exercise, but for stock that is not yet liquid and has no guarantee of becoming liquid if the company is not successful – this is known as ‘dry’ or ‘phantom’ taxation.

In recent years many startup employees have spoken out about being burned by these 90 day exercise windows and not receiving a chunk of compensation that they should be entitled to – such as Ali Khajeh-Hosseini at RightScale. This has started a trend of startups offering more generous post-termination exercise windows. Ali himself has since started a company himself (Infracost), where he’s implemented a 10 year post-termination exercise window.

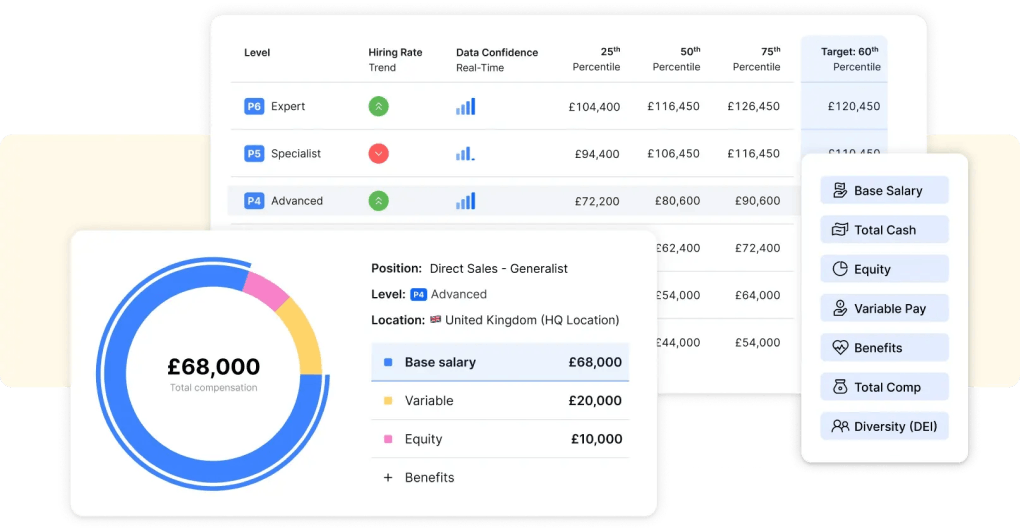

Step 7: Get access to equity benchmarks to calculate new hire equity grants

At this point you’ve decided on the overarching equity philosophy and rationale – how much equity to set aside for employees, which employees will receive equity, in what form, and with what vesting requirements.

The next step is to calculate how much equity compensation an employee should actually receive when they join the team.

So how do you do that?

Well, equity compensation typically varies depending on:

- Job role – some roles are more likely to have equity incorporated into their total compensation than others e.g. software engineers in tech companies

- Job level – just like base salary, the more senior an employee, the more equity compensation they typically receive

- Company stage, size, and industry – it’s more common for some company types to offer equity as part of total rewards than others e.g. early-stage tech startups

- Target percentile – the overarching equity philosophy a company lands on will dictate how competitive their equity compensation should be compared to the market e.g. an early-stage startup might opt for 75th percentile equity to balance lower base salary offers, or equally a more established company may also opt for 75th percentile but for all aspects of compensation to attract the top talent on the market.

💡Want to know what the typical startup equity compensation package actually looks like?

Head to the section below ‘Typical equity compensation for startup employees: insights from Ravio’s equity benchmarks’ where we’ll dive into Ravio’s data on this.

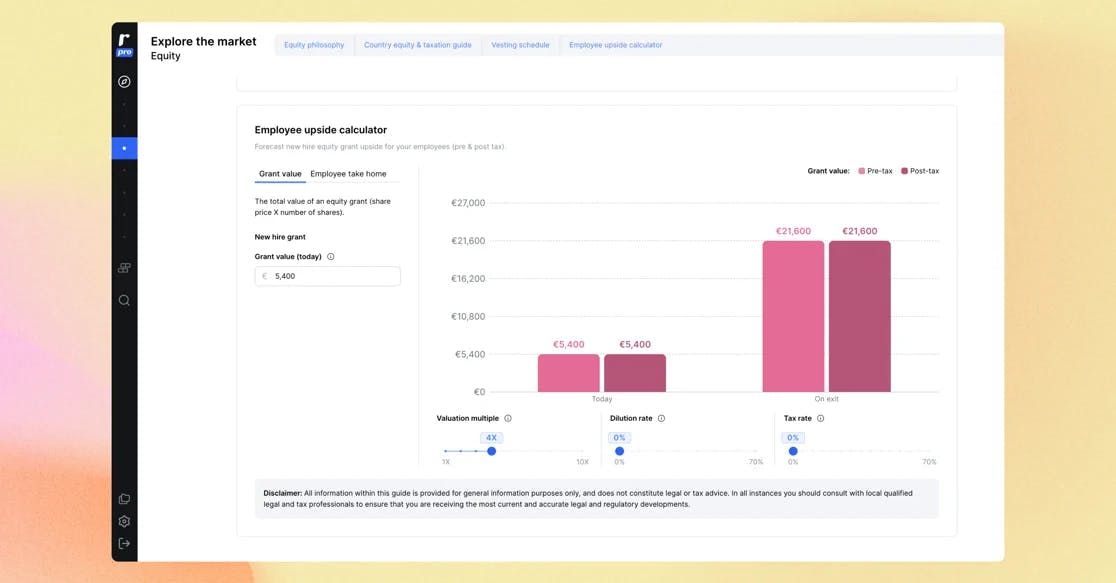

This means that access to accurate equity benchmarks (like Ravio’s) is the foundation to determining the equity compensation package for each employee – ensuring you have the data to make an informed offer based on the market.

Step 8: Build equity compensation bands

The equity benchmarks should then be used to build a framework for calculating new hire equity grants.

When it comes to designing that foundation, there are two ends to the scale.

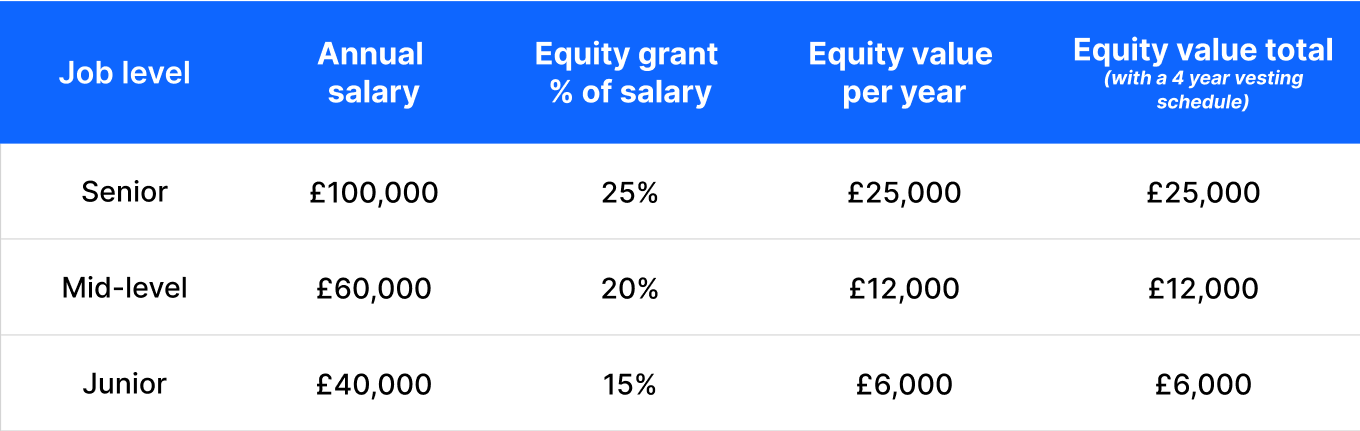

Some companies opt for a simple approach, using a base salary multiplier which varies depending on pre-agreed factors like employee role or seniority level – which looks something like the below:

This simplistic approach is the standard for most companies – many even use a ‘finger in the air’ approach based on what seems fair or the negotiation that happens during hiring.

But this isn’t best practice.

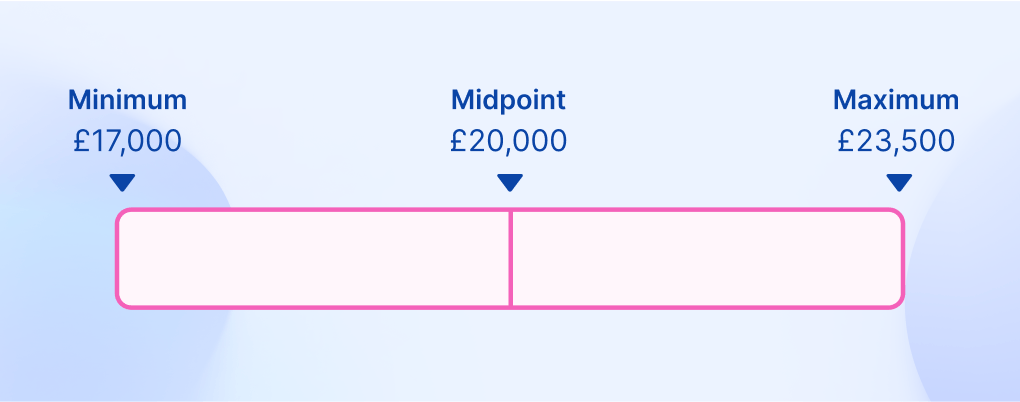

The best practice approach is to design an equity band structure, in the same way as you would with salary bands. This creates a granular framework which informs the range of compensation that is possible for each job role, job level, and location within the organisation structure.

This kind of detailed equity band framework is particularly valuable for companies that prioritise fair and equitable pay within their compensation philosophy – to ensure a consistent structure behind how equity decisions are made. It also brings structure to equity compensation progression for companies that intend to issue equity refresh grants or increase equity at promotion.

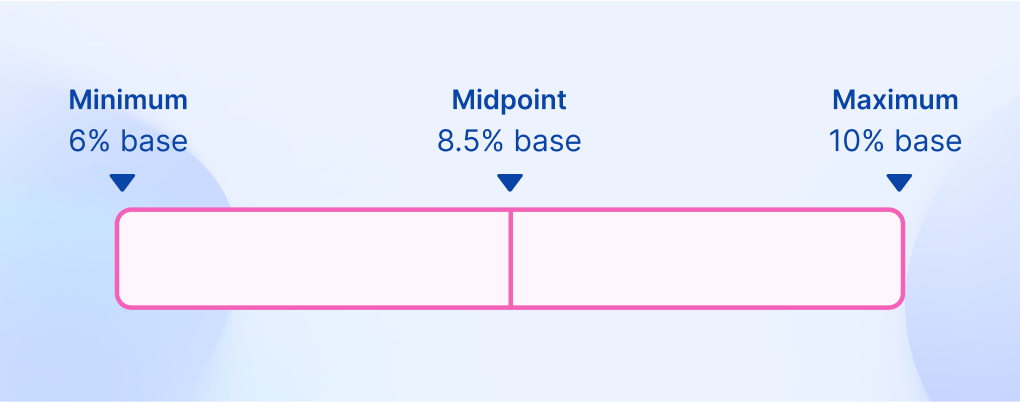

The bands could be set up with the midpoint and range based on actual grant value in the company or employee’s currency, in the same way that salary bands are:

Or, depending on how the company grants equity, the midpoint and range could be based on a percentage of base salary, a percentage of ownership in the company, or an actual number of shares.

Because it’s so unusual for companies to have this kind of clear structure and rationale behind equity compensation, there’s an opportunity to set your company’s compensation approach and employer brand apart from talent competitors, simply by establishing such a framework.

Step 9: Decide whether equity refresh grants will be included in ongoing compensation reviews

Equity refresh grants (or equity refreshers) are when additional equity is granted to an employee throughout their tenure.

This is typically an employee retention mechanism to give additional financial incentive to stay with the company, complete with a new vesting schedule.

It’s common for equity refresh grants to be part of the overall compensation review process, rewarded to employees either to bring them back in line with shifting equity benchmarking data or to reward high performance. It’s also typical to grant additional equity at promotion to reflect the fact that equity typically increases with seniority level.

Deciding how your company will approach equity refresh grants is an important part of the overall approach to equity compensation.

Step 10: Create clear documentation and guidance for employees on equity compensation

Employee communication and education is, of course, a key part of any compensation plan.

There are two key components to this:

- The legal part. Designing an equity grant agreement to go alongside the employment contract for all new hires.

- The education part. Ensuring employees understand what equity compensation is, how the company thinks about employee equity, and the value of their equity package.

For the equity grant agreement, we’d always recommend consulting with a lawyer who knows what they’re doing.

When it comes to employee education, it can be complex.

Equity is a complex topic in the first place. At the same time, the value of equity also fluctuates and changes throughout a startup’s journey. Plus, some companies may offer equity refresh grants as part of their performance and progression structure – all adding further complications.

Here’s a few ideas on how to effectively communicate the value of equity compensation to employees:

- Organise equity 101 education for employees. Support employees with understanding the basics of equity through an upskilling exercise. Depending on your internal comms preferences, this might mean providing written resources and FAQs as part of the onboarding process, or an all-hands presentation that is recorded to refer back to, or something else.

- Include equity in company updates. Don’t think of equity as a ‘one-and-done’ topic of conversation for your team – great communication means ensuring regular touchpoints and opportunities to discuss and ask questions. And given that equity compensation is tied to company success, it can be useful to include an equity update within your company updates on e.g. funding rounds, valuations, future plans for liquidity events – what does this mean for the value of each employee’s equity compensation?

- Include equity in performance review conversations. We’ve seen throughout this guide that market standard equity compensation varies depending on the job role and job level, so many startups include increases in equity compensation as part of career progression – if that’s true for your company, make sure you’re communicating about the value of increased equity throughout the performance review cycle.

Typical equity compensation for employees: insights from Ravio’s startup equity benchmarks

What is the typical equity compensation package for a startup employee?

As we’ve seen throughout this guide, reliable equity benchmarking data is core to answering this question – so, let’s take a look at some insights from Ravio’s compensation dataset.

We’ll focus on a few key questions that, as we’ve seen, are important decisions to make when planning an equity compensation structure:

- Do all employees typically get startup equity – or only certain employees e.g. founding engineers or company leaders?

- What is the most common vesting schedule for startups?

- How does equity compensation vary across different roles, levels, and locations?

Which employees typically receive equity compensation in startups?

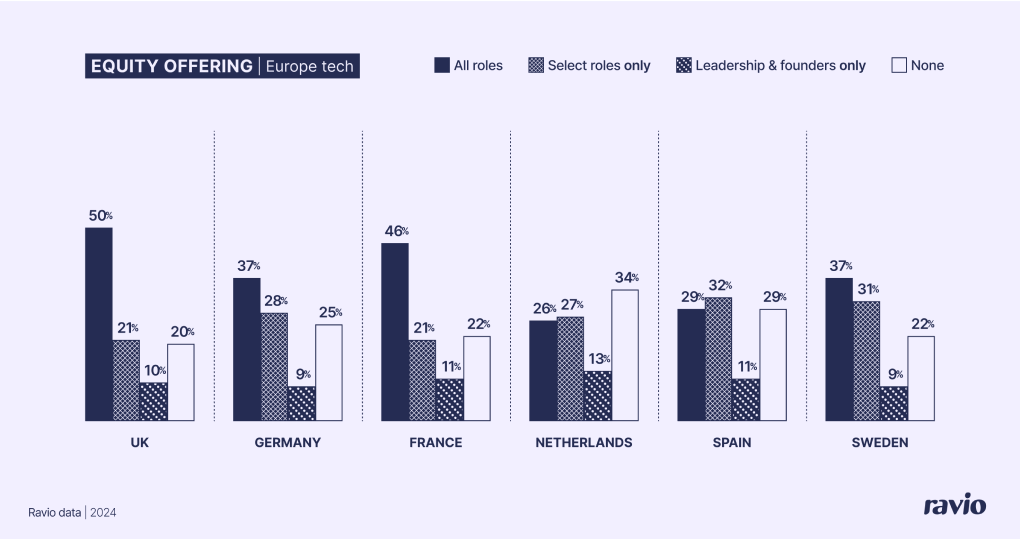

There’s actually a significant amount of variance across different countries in Europe in terms of which employees are granted equity as part of their total rewards package – and this also varies depending on company stage, and industry too.

To take location as an example, we can see from Ravio’s data that in France and the UK it’s very common for all startup employees to receive equity, with 46% of companies offering equity compensation to all employees.

In comparison, in the Netherlands, Sweden, and Spain less startups offer equity compensation to all employees (26%, 37%, and 29% respectively), and it’s more common that only certain employees will receive equity.

What is the most common equity vesting schedule for startups?

Ravio’s data shows that the most popular vesting structure across European tech companies is:

- Vesting period: 4 years

- Vesting frequency: monthly

- Cliff: 1 year

With 62% of companies taking this approach.

How does startup equity vary per role?

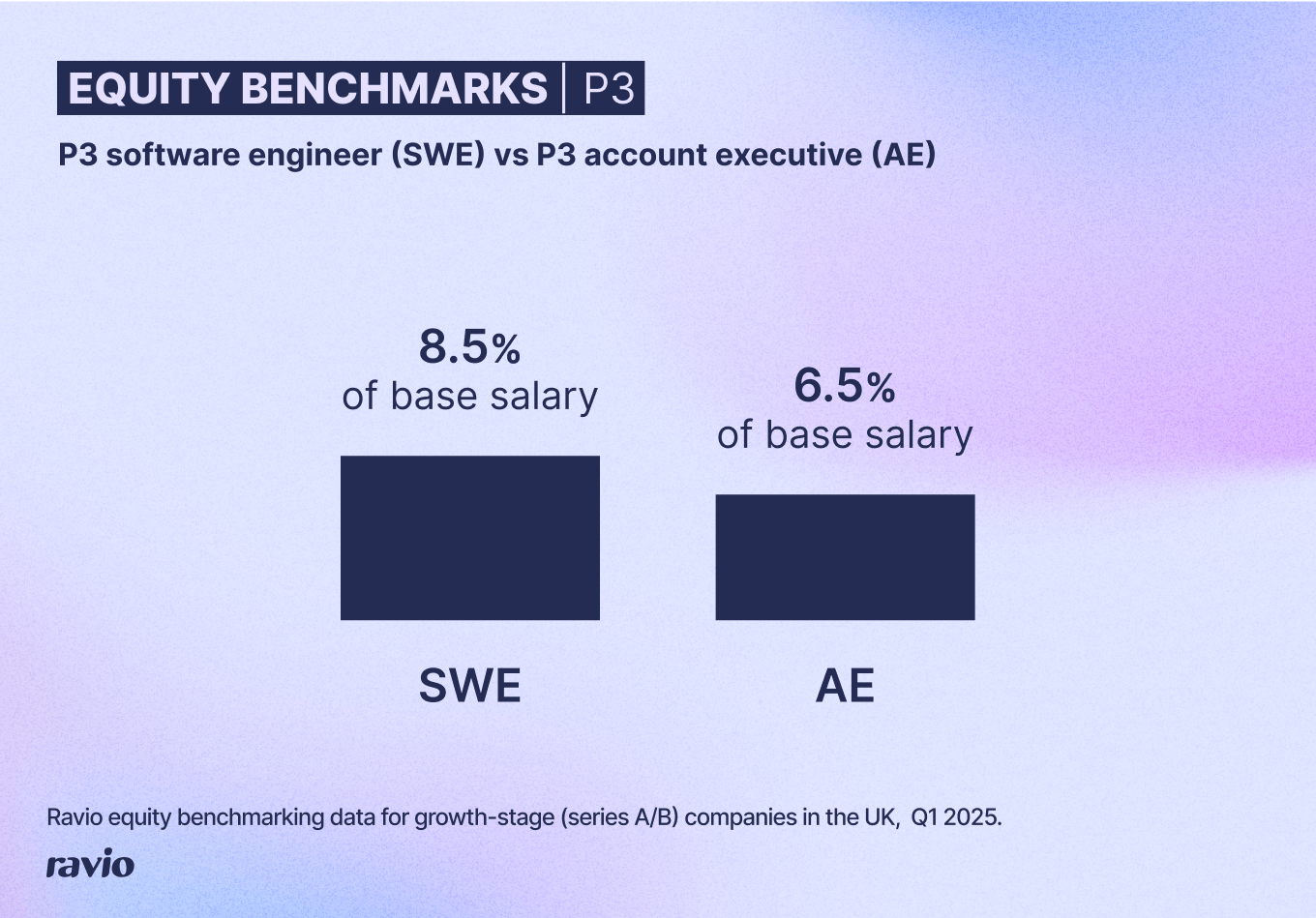

To understand how equity compensation typically changes depending on job role, let’s take a look at the example of a P3 software engineer and a P3 account executive at a typical growth-stage startup in the UK.

The value of equity compensation depends entirely on a company’s valuation, and their current share price and strike price – which makes it difficult to compare equity compensation across companies.

For this reason, all data in the following section uses Ravio’s equity benchmarks (correct as of January 2025) for a company valued at £80 million, with a share price of £3.00, and a strike price of £0.01.

Ravio uses the Black-Scholes methodology to calculate the fair market value of each equity grant in its database in order to determine comparable and consistent equity benchmarks – which enables Ravio to standardise and compare different types of equity with different parameters across any company.

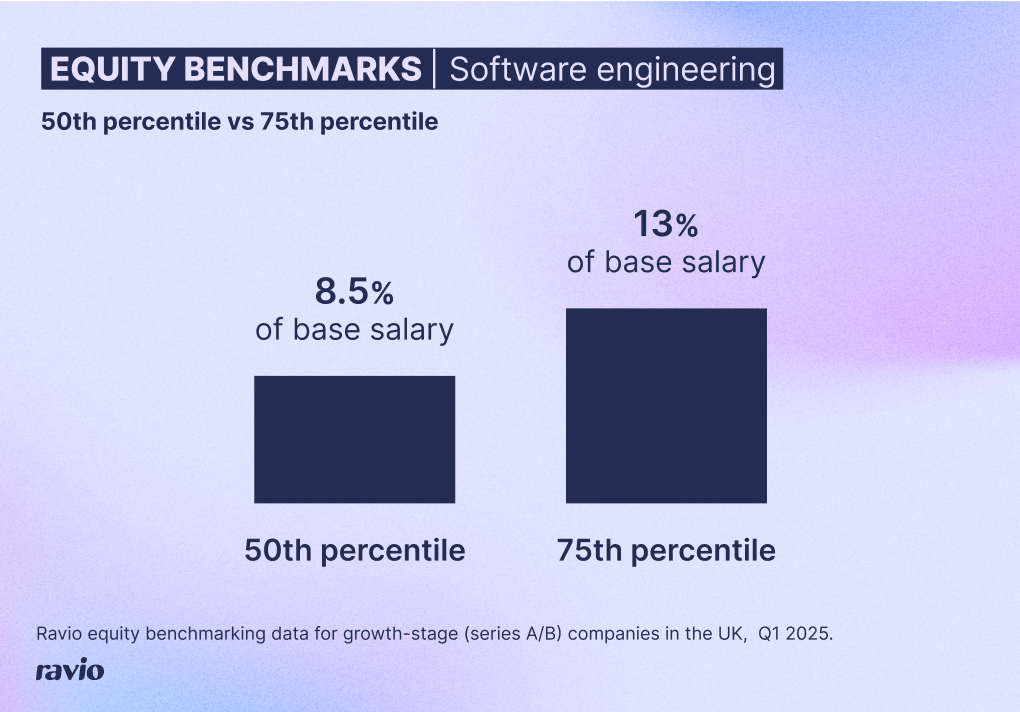

So, according to Ravio’s data, the P3 software engineer at a growth-stage UK startup would receive a new hire equity grant of 8.5% of the base salary. The median salary for this profile is £67,000 – so the new hire equity grant would be £5,700 in equity per year over a typical 4 year vesting period, or £22,900 total, for this role and level.

For a company with the same profile but which targets the 75th percentile, the typical new hire equity grant is higher: 13% of the base salary. The 75th percentile salary is £74,600, so £9,698 in equity per year or £38,792 in total over a typical 4 year vesting period.

Looking at a P3 account executive role instead, Ravio’s data shows that new hire equity grants in commercial roles are typically slightly lower than in tech roles – whilst, on the other hand, sales roles are more likely to have a variable pay component through on-target earning incentives.

The typical grant is 6.5% of base salary. At the 50th percentile the base salary for this role is £53,500, so the grant would be worth £3,400 in equity per year, or £13,600 in total over a typical 4 year vesting period.

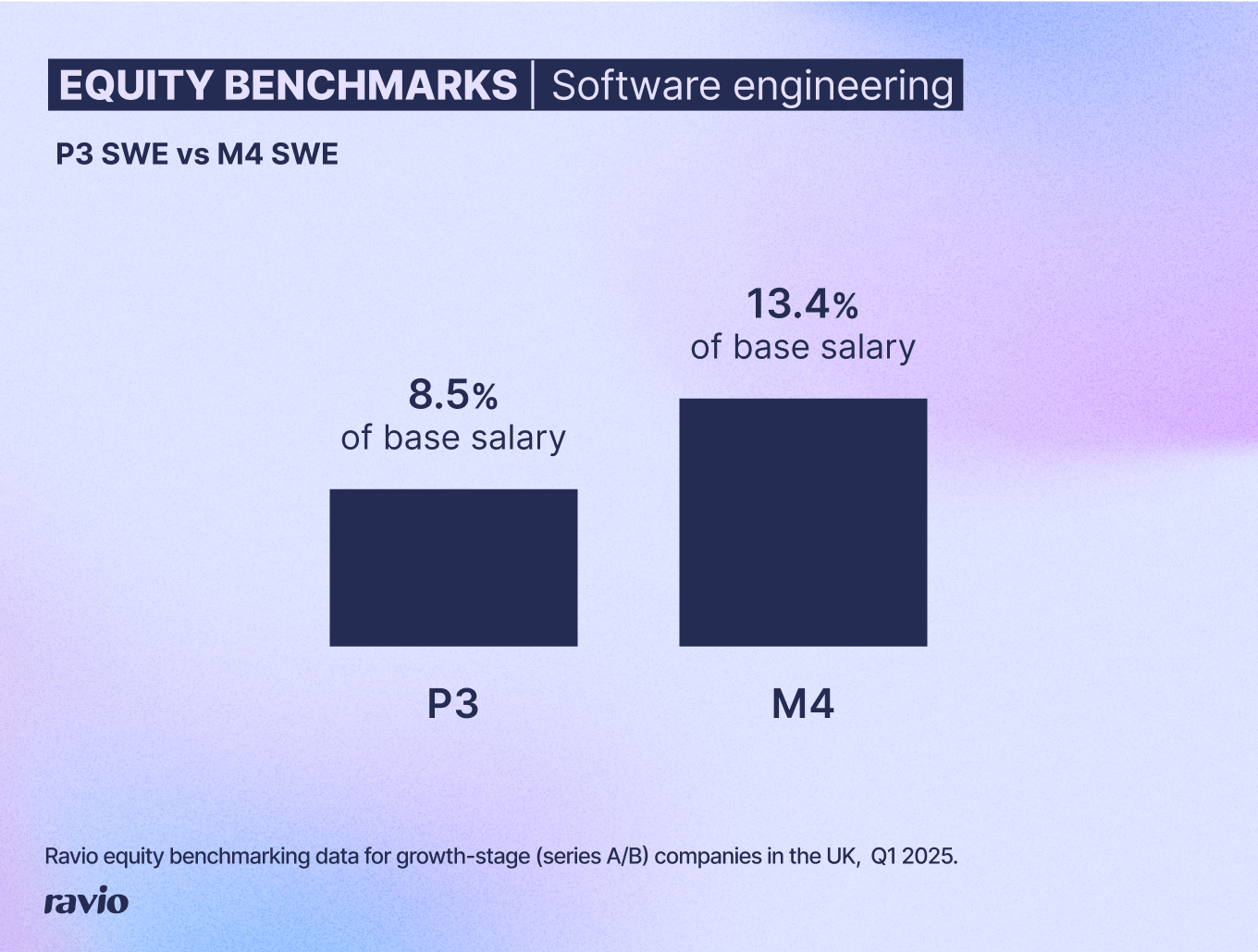

Equity compensation also increases with job level, in the same way as salary.

For instance, the typical equity grant offered to an M4 software engineer (director level) at that same UK growth-stage startup company profile is 13.4% of base salary – considerably higher than the equity compensation for the P3 software engineer.

Equity compensation at early stage startups vs series A vs series B vs series C

Let’s take the same example of a P3 software engineer and a P3 account executive in the UK to explore how typical employee equity depends on the funding stage of a startup – again remembering that the value of a new hire equity grant entirely depends on the valuation of the company, so using the example of Ravio equity benchmarks based on a company valued at £80 million, with a share price of £3.00, and a strike price of £0.01.

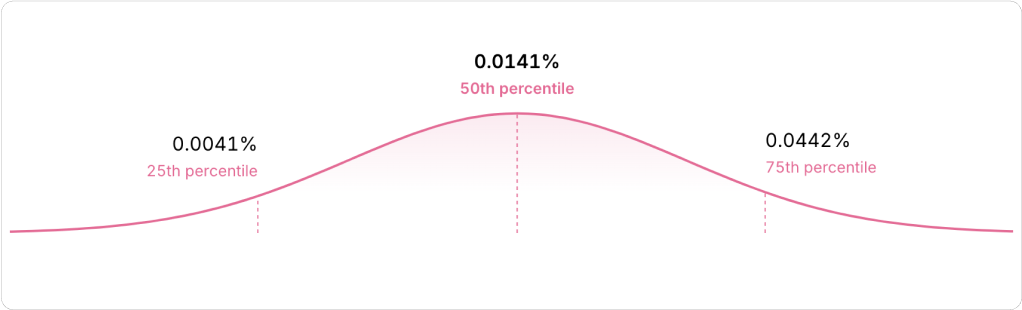

At early-stage startups, equity compensation is typically presented as a percentage ownership.

For a P3 software engineer, we can see from Ravio’s data that the median equity benchmark is 0.0141% company ownership.

For a P3 account executive the equity grant is typically slightly lower, with the median equity benchmark being 0.0111% – largely reflecting the relative importance of tech talent in startups.

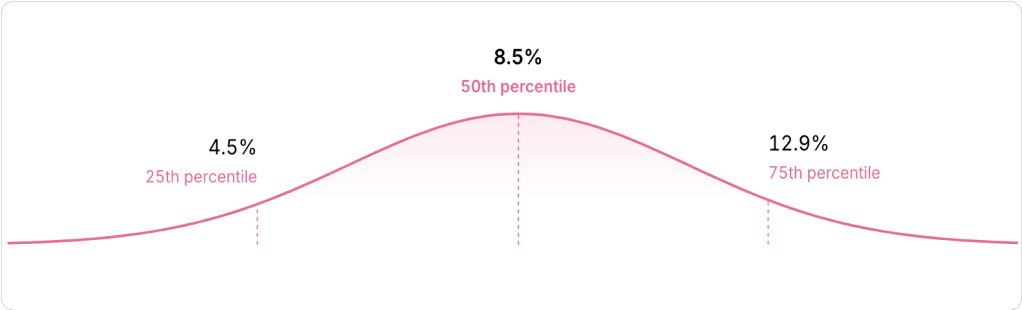

At growth-stage startups (series A and B) it is typical for companies to grant equity as a percentage of base salary.

For a P3 software engineer in a series A or B startup in the UK, the median equity benchmark is 8.5% of base salary.

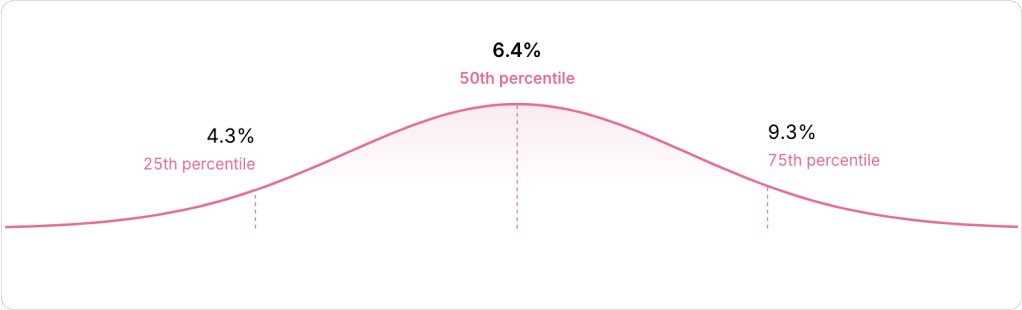

For the P3 account executive, the median equity benchmark is again a little lower, at 6.4% of base salary.

Late-stage startups (series C+) also typically grant employee equity as a percentage of their base salary.

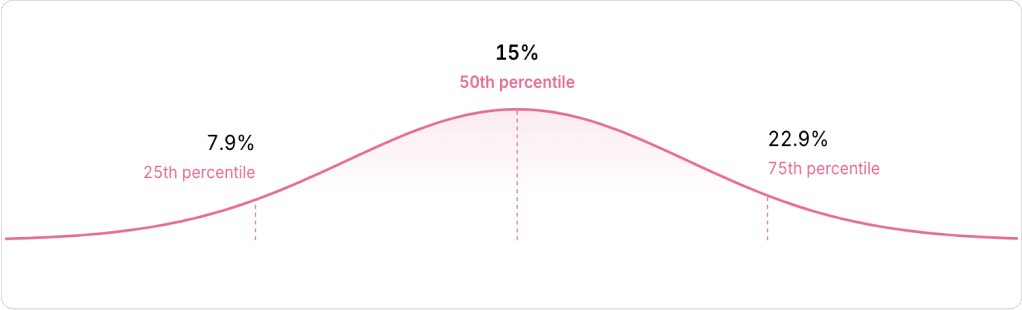

We can see from Ravio’s data that there’s a significant increase in typical employee startup equity as companies move into their late stage and become much more established. For instance, the same P3 software engineer would receive a new hire equity grant of 15% of their base salary – and their base salary will also be higher as salaries also typically increase with company stage.

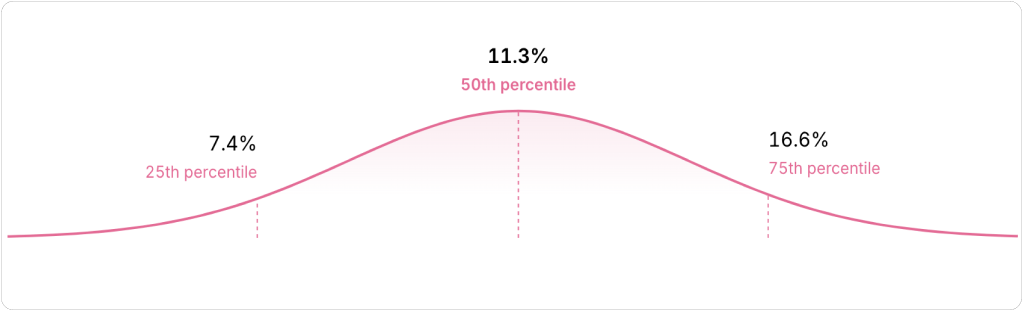

The same is true with the P3 account executive, with the new hire grant jumping up to 11.3% of base salary – still lower than software engineers, but a significant increase compared to growth stage startups.

📊 Get access to real-time startup equity benchmarks

Book a demo to see how easy it is to find the data you need on equity benchmarks in Ravio – including how equity varies depending on funding stage, job role, location, and more.

Equity compensation FAQs

What is equity compensation?

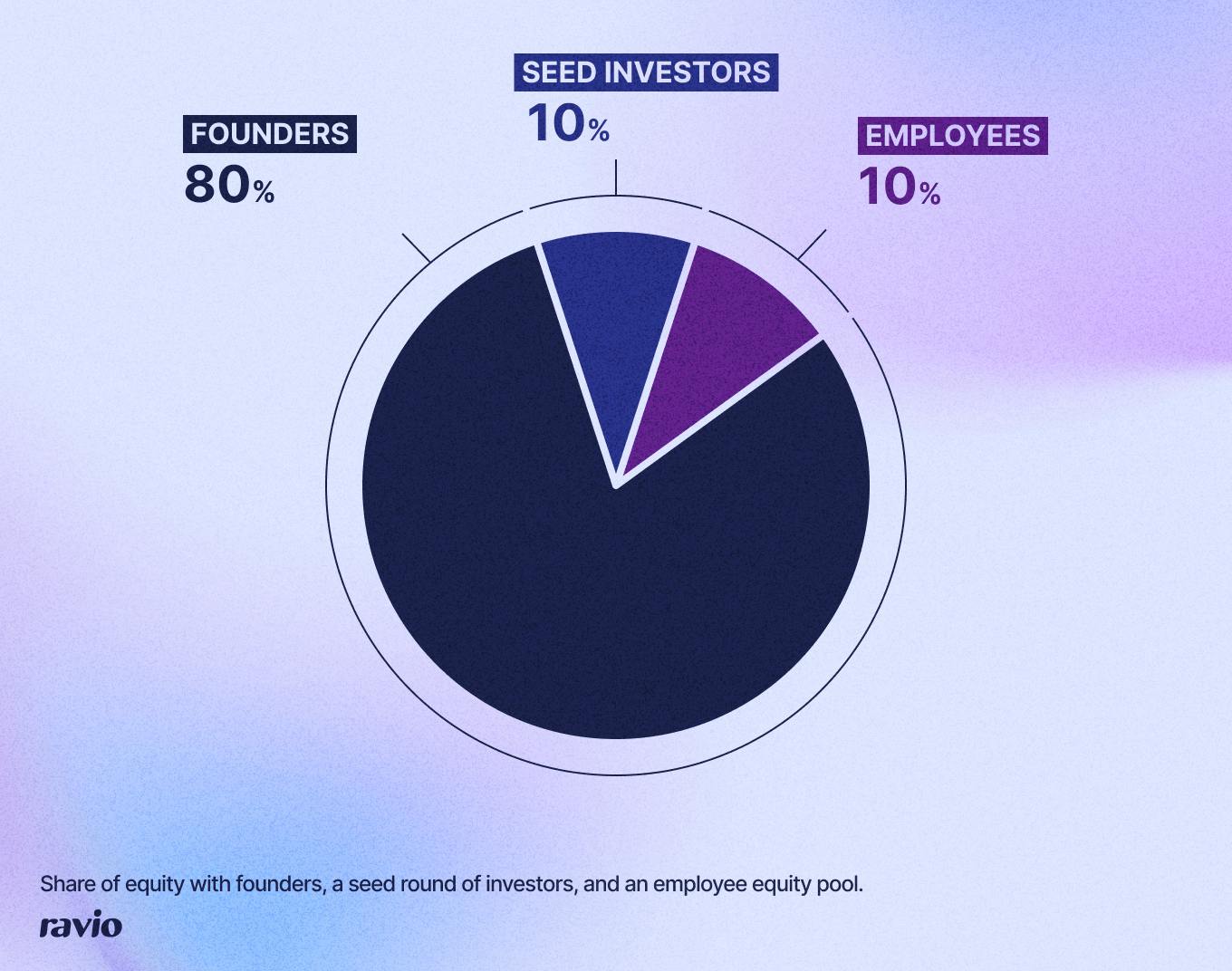

In very simple terms, a startup’s equity refers to the ownership of the company.

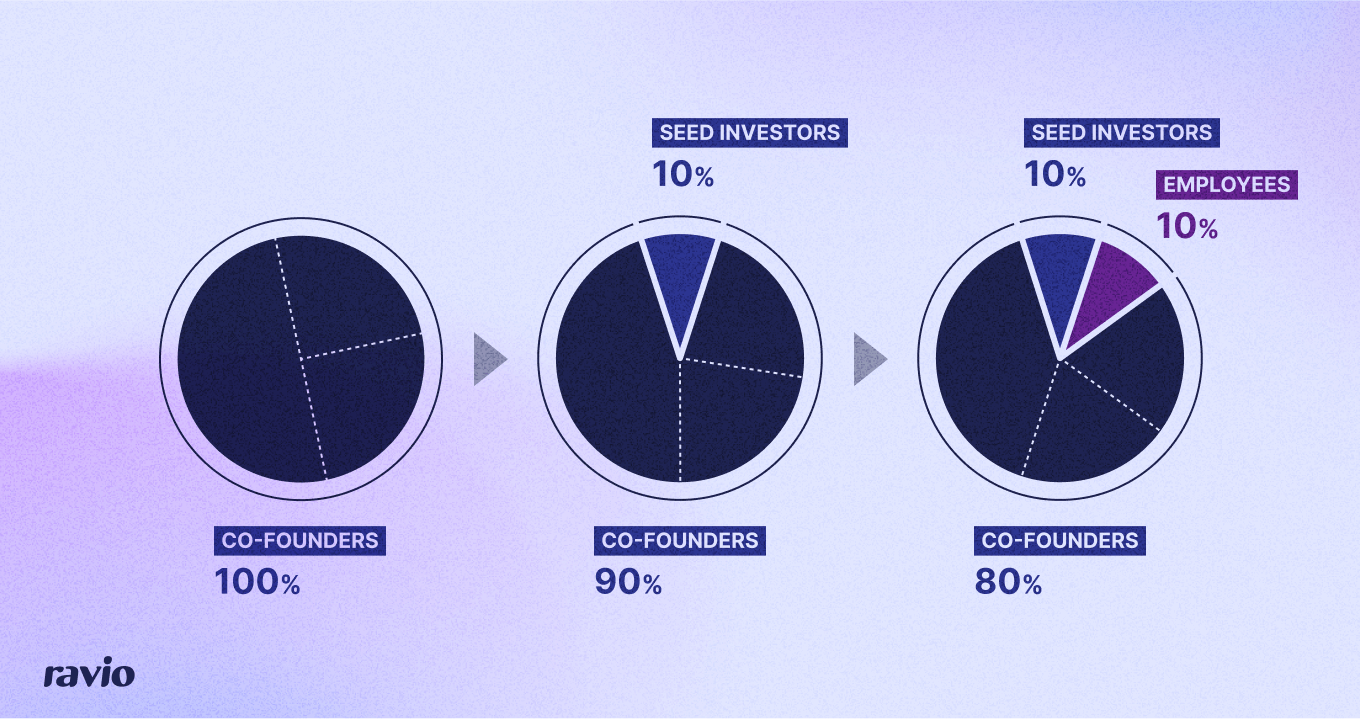

A common analogy is to imagine equity in a startup as a cake or pie. The pie represents the whole company, with slices cut out of the pie as equity or ownership in the company is given to other people or entities – and those slices can be different sizes too.

If you start a company as a sole founder, you will initially own the business in its entirety and therefore have 100% of the equity.

In this instance, the sole founder has 100% of the pie.

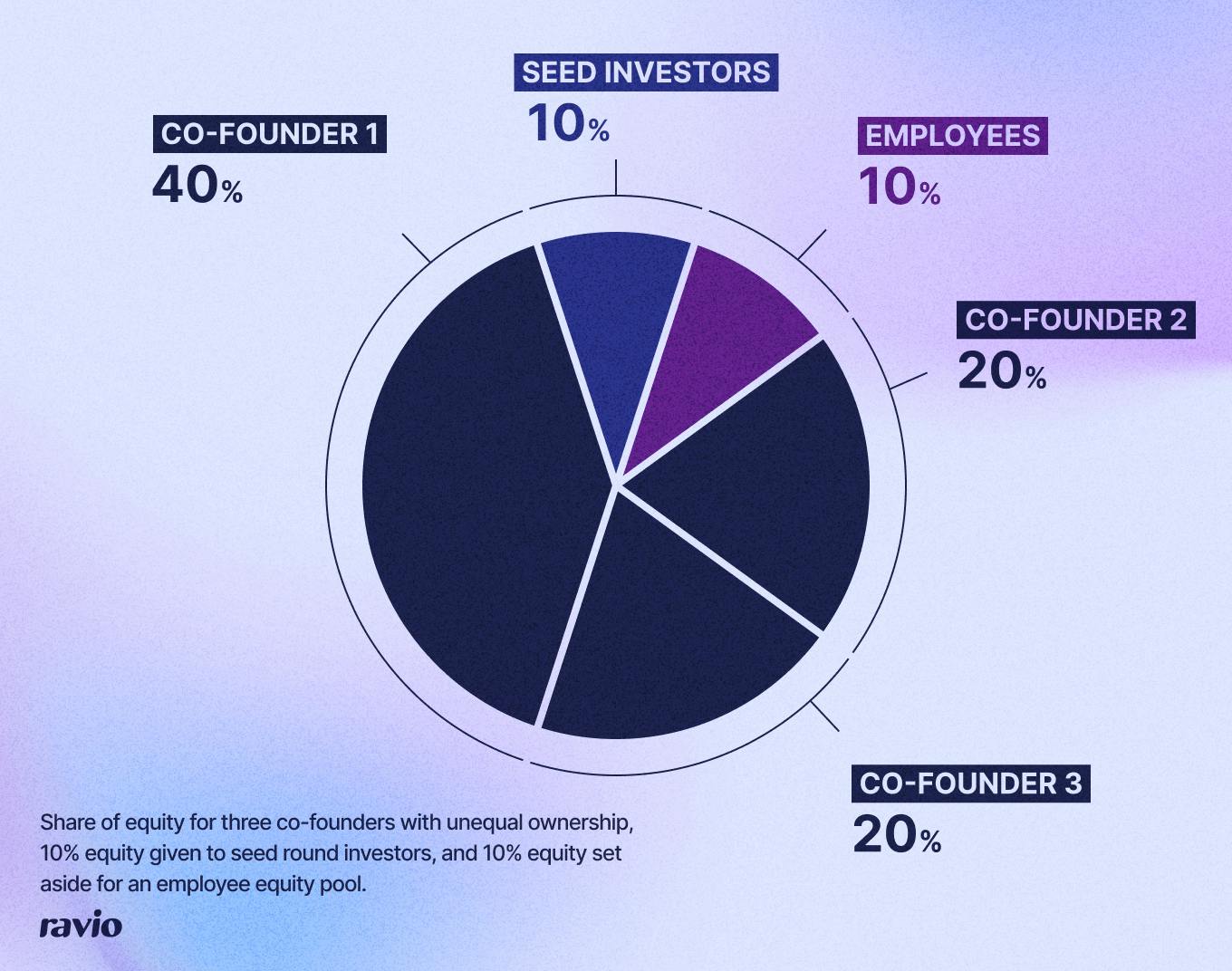

If you’re a group of three co-founders, ownership and equity is initially split between the three of you. It might be an divided evenly with each founder holding 33.3% equity.

Or it might be divided unevenly to acknowledge, for instance, that one founder will contribute more time or work into the company (known as a dynamic equity split) – or simply to give a decision-making mechanism when difficult decisions need to be made and founders are split.

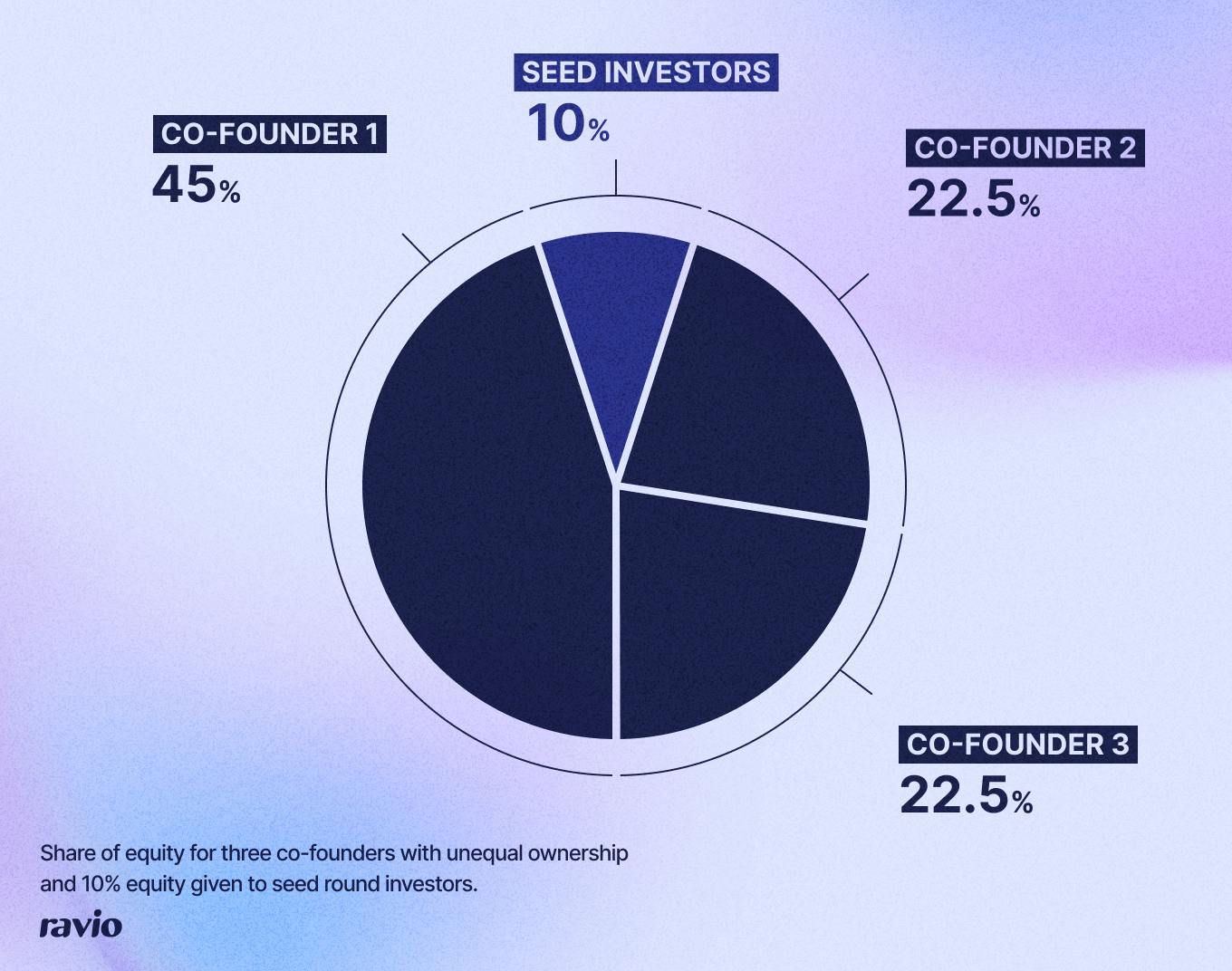

If you decide to raise funds through venture capital, some of the equity in the company is given to the investor(s) in exchange for cash to use to build and grow the business.

The investors are making a calculated bet that the startup is successful and the equity they own will become much more valuable than the cash investment they put in.

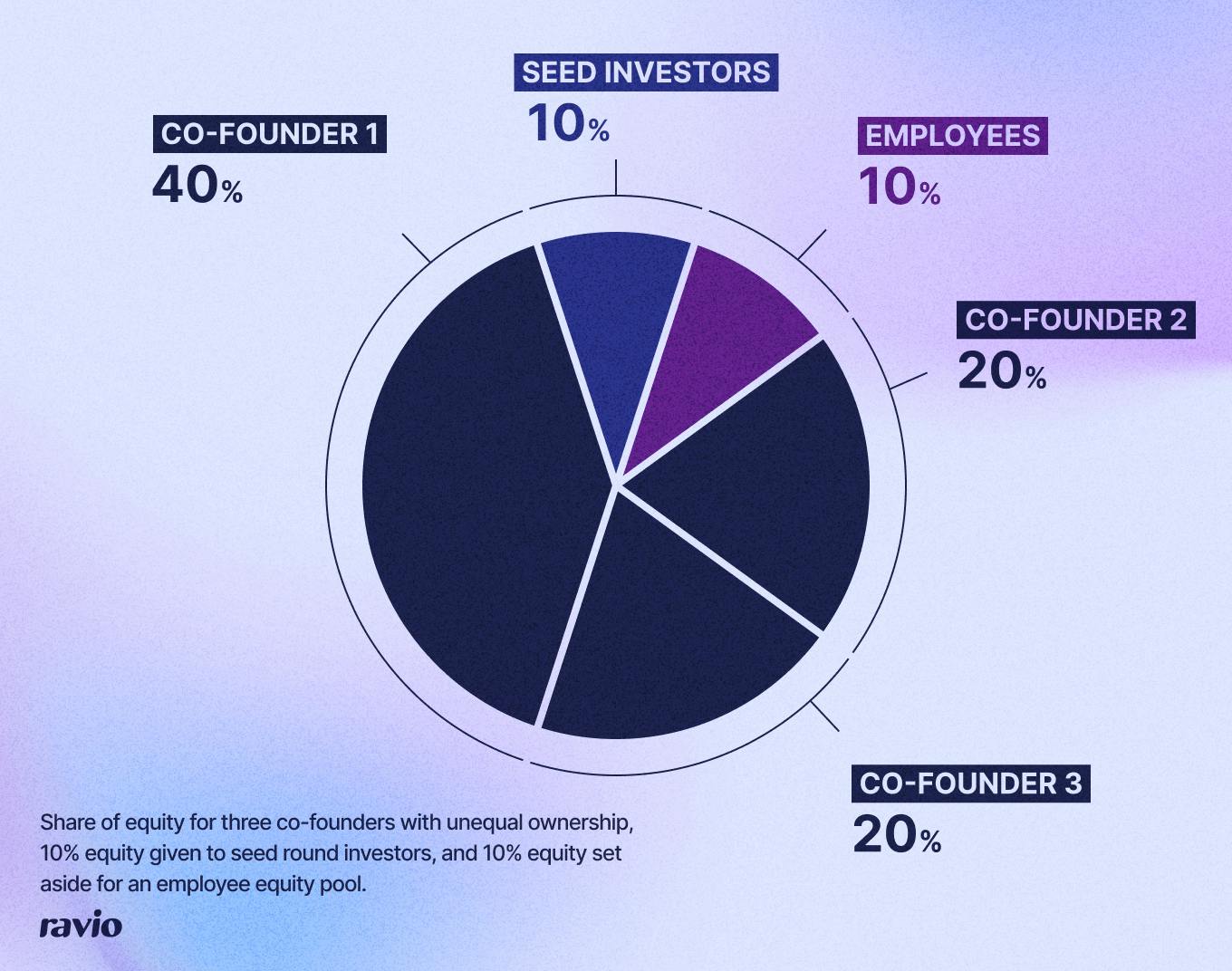

When you start hiring additional employees to work on the startup, you might decide to also give those employees equity in the company.

This is equity compensation – employees are granted an ownership stake in a company as a form of payment for their work. If the startup does well and increases its value over time, then the equity the employee owns will also increase in financial value.

What is dilution in equity compensation?

Dilution refers to a decrease in equity or ownership for existing company shareholders, occurring when the company issues new shares.

When new shares are created or issued it means there are more shares in existence than previously, and so each of those shares represents a smaller percentage of ownership in the company.

So, in the very early days of a startup the company may be owned entirely by the founders – three founders with a 50/25/25 split, for instance.

If that company then decided to raise a seed round of VC investment and exchange 10% company equity for cash to build the business with, then the percentage ownership of each founder will be ‘diluted’ to allow for this.

And the same is true if the founders decide to offer equity compensation to employees. They might opt to set aside a 10% employee equity pool, which then further dilutes their percentage ownership.

Later investment rounds, and eventually the public sale of shares, will further dilute the proportion of equity for all existing owners.

However, dilution does not typically mean an actual reduction in the value of the equity – because the value of the company should continue to increase at the same time, so each individual share becomes worth more.

What is vesting in equity compensation?

Vesting is the process of transferring legal ownership of something from one person or entity to another – so in equity compensation vesting refers to the transfer of shares from the company to the employee.

Vesting typically takes place gradually over a set period of time to incentivise employees to remain at a company, with the employee only owning the equity, and therefore the ability to exercise it, once fully vested. This is known as the vesting schedule.

There are three key elements that go into a vesting schedule:

- Vesting period: the overall length of time between an equity agreement being made with an employee and the point at which the designated shares have fully vested and ownership has 100% transferred to the employee.

- Vesting frequency: how often shares vest within the vesting period i.e. how often a percentage of the total designated shares are transferred to the ownership of the employee – typically monthly, quarterly, or annually. For potential employees, a more frequent vesting schedule is more attractive, meaning that they’re less likely to leave equity on the table if they do end up leaving the company before the end of the vesting period.

- Cliff: a period of time which must pass before the shares begin vesting, ensuring that the employee contributes value to the company before they receive their equity compensation and to account for mishires, underperformance etc in the very early days of employment.

The vast majority of startups opt for a 4 year vesting schedule with a 1 year cliff and a monthly vesting frequency.

What is a cliff in equity compensation?

Cliff refers to a period of time defined by the employer which must pass before an employee’s equity begins vesting i.e. they gain ownership of the shares.

This is primarily to ensure that the employee contributes value to the company before they receive their equity compensation and to account for mishires, underperformance etc in the very early days of employment.

The most common cliff is one year, which means the employee must stay with the company for one year before their equity starts vesting.

What is a strike price in equity compensation?

The strike price is the pre-agreed and fixed price it will cost the employee to buy one share in the company when they exercise their equity, also known as the exercise price.

It’s included as part of the equity grant agreement when equity is granted as stock options – with stock options employees are given the right to buy shares at a fixed price. If the company is successful its stock will increase in value over time and the employee will make money by buying their allotted shares at the fixed strike price and selling them at the market price.

Designated strike prices vary from company to company, but they’re typically determined by the company’s share price at the time an employee joins the company (also known as the fair market value). Companies will typically, therefore, adjust their strike price for new employees as the company grows and its valuation changes.

What is a new hire equity grant?

A new hire equity grant is the equity compensation that an employee receives when they first join a company – granting them a stake in the company as part of their total compensation package.

What is an equity refresh grant?

An equity refresh grant is when additional equity compensation is issued to an employee who already has equity in the company, as a way to recognise and reward the employee’s performance – similar to a performance increase of salary.

The initial equity compensation offered to an employee as part of their job offer is typically known as a ‘new hire equity grant’. An equity refresh grant would issue additional equity on top of what was agreed within their new hire equity grant.

What is a cap table?

A cap table is a document which breaks down the ownership of a company: who has equity in the company, what percentage ownership they have, and what share class they own – companies can have several different classes of shares with different ownership rights attached to them.

This includes equity granted to employees as equity compensation, so cap tables are an important part of equity management.

What does it mean to exercise your shares as an employee?

In simple terms, to exercise your shares means to buy those shares.

When employees are granted equity compensation it’s typical for a vesting period to be in place, which means that the ownership of the equity is gradually transferred from the company to the employee over a set period of time (typically 4 years with a 1 year cliff).

Only equity that has vested can be exercised i.e. converted into actual shares in the company, and once exercised the shares can be sold and converted into cash.

In the case of stock options where the equity agreement gives employees the right to buy shares at a fixed strike price, exercising the options means actually buying those promised shares at the strike price, giving the employee actual shares in the company.

In most cases, employees are restricted by the need for a liquidity event to occur before they are able to exercise their options – IPO, merger or acquisition, and tender offer being the main liquidity events in a startups lifecycle. This restriction is put in place to prevent employees selling shares in the company on to external parties, who would then be on the cap table of the company and have ownership rights.

Most companies also include a post-termination exercise period (PTEP) in their equity grant agreement documentation.

This means that if an employee leaves the company, they have a set window of time e.g. 90 days in which to exercise their options, otherwise they will expire. It’s also typical for the equity to stop vesting immediately when an employee’s contract is terminated.

What is an equity only role?

An equity only role refers to a compensation package where an employee is rewarded solely through equity in the company – no base salary and no variable pay.

Equity only roles can arise in the early stages of a startup when there is limited cash available to compensate founding employees with, and so they are offered equity as an incentive to join the company.

They should then be offered a base salary as soon as possible, as there’s no guarantee that equity compensation will ever have any financial value, meaning the employee could effectively be working for free.

How much equity should you give to the first employee?

It’s common for the first few employees to join a company after the founders (often known as founding employees) to be granted a disproportionate amount of equity compensation, in recognition of the risk they’re taking to join joining a startup at such an early stage – and potentially also to balance a lower salary offer if the startup has limited cash to offer.

The typical equity grant for first and founding employees ranges between 1-3% for a set number of employees e.g. the first five hires receive 1% equity each.

However, this isn’t best practice because it’s arbitrary – there’s no clear logic and rationale behind how the equity is being granted. This means that there will be inconsistencies and inequities in employee compensation from the very start of the company.

The best practice approach is to make a value judgement based on how much risk each individual employee is taking – taking into account the company’s position as well as the employee’s i.e. what role, company, compensation package are they leaving behind to join the startup.

How do I determine the right equity pool size for my company?

The size of your employee equity pool requires balancing talent attraction with founder control. Avoid arbitrary percentages and take a strategic, bottom-up approach instead.

Build from your hiring plan: Model out employees you plan to hire over the next 18-24 months by role and seniority. Use equity benchmarking data (like Ravio's) to determine market-rate equity grants for each position. This gives you the actual equity needed to execute your hiring strategy.

Early-stage companies often allocate 10-20% to employee equity pools, but your specific needs may vary significantly based on your hiring strategy and market positioning.

Key factors to consider:

- Your hiring timeline and planned headcount

- Market benchmarks for equity by role and level

- Your compensation philosophy e.g. are you offering 75th percentile equity to offset lower salaries?

- Expected future funding rounds and dilution impact

- Ongoing equity progression – will you increase equity when employees are promoted? Will you offer equity refresh grants for high-performing or long-tenured employees?

Repeat this analysis before each funding round or strategic shift, as your hiring plans will evolve with company growth.

Should we offer equity to all employees or just certain roles/levels?

This decision depends on your compensation philosophy, company values, and practical considerations.

Key decision factors include:

- Compensation philosophy: How does equity fit your overall rewards strategy?

- Fairness considerations: Universal equity can reduce pay disparities

- Administrative complexity: Selective equity is simpler to manage – especially if you have employees across multiple locations with different legal and taxation considerations.

- Employee preferences: Not all employees prefer equity over cash – you might want to make the balance their choice in a flexible compensation model.

If you’re only offering compensation to certain employees, the most common selection criteria are:

- Executive team and leadership only

- First hires and early employees only

- Specific functions (e.g., engineering, product roles)

- High-impact or hard-to-hire roles

The most important factor is having a well-defined compensation philosophy that guides consistent, fair decisions about who receives equity.

For detailed analysis and expert insights on this decision, read our complete guide: Should you grant equity compensation to all employees?

How much equity should you give to the first employee?

It’s common for the first few employees to join a company after the founders (often known as founding employees) to be granted a disproportionate amount of equity compensation, in recognition of the risk they’re taking to join joining a startup at such an early stage – and potentially also to balance a lower salary offer if the startup has limited cash to offer.

The typical equity grant for first and founding employees ranges between 1-3% for a set number of employees e.g. the first five hires receive 1% equity each.

However, this isn’t best practice because it’s arbitrary – there’s no clear logic and rationale behind how the equity is being granted. This means that there will be inconsistencies and inequities in employee compensation from the very start of the company.

The best practice approach is to make a value judgement based on how much risk each individual employee is taking – taking into account the company’s position as well as the employee’s i.e. what role, company, compensation package are they leaving behind to join the startup.

How do we benchmark our equity offers against market rates?

Accurate compensation benchmarking is crucial for competitive equity offers that are aligned with market data.

Benchmarking tools like Ravio provide equity benchmarking data that accounts for company stage, industry, location – as well as how companies typically offer equity across different groups of employees e.g. level of seniority.

Your benchmarking should consider company stage (early-stage equity is typically expressed as ownership percentage while growth-stage uses salary percentage), role and seniority (engineering and product roles typically receive higher equity than commercial roles), location (there's significant variation across European markets), and your target percentile that aligns with your compensation philosophy.

Update your benchmarks annually or before major hiring pushes, as market rates evolve with funding cycles and talent competition. Reliable benchmarking data is foundational to building fair, competitive equity programs that attract top talent while managing dilution effectively.

What are the legal and tax implications for companies implementing equity compensation?"

Equity compensation creates significant legal and tax obligations that vary by jurisdiction and equity type. Proper planning is essential to avoid costly compliance issues.

From a legal perspective, equity grants are securities transactions requiring proper documentation and potentially regulatory filings. You'll need to ensure compliance with employment law. In the UK, for instance, employers must report to HMRC when equity awards are made to any recipient, including employees.

In terms of tax implications, in most cases there are employer taxes like national insurance or payroll taxes when employees exercise their shares – and these taxes vary from country to country, so if you employ team members in multiple locations you’ll need to adhere to each location’s employment law.

Many countries also have tax-advantaged schemes like EMI (UK), BSPCE (France), or KEEP (Ireland) which come with different tax rules to incentivise employers to offer equity compensation to employees – again, another thing to consider.

Different equity types create different implications too. Stock options generally create no immediate tax for the company with obligations arising at exercise, RSUs typically create tax obligations at vesting, and VSOPs are treated as cash bonuses when paid out.

Always consult qualified legal and tax advisors familiar with equity compensation in your relevant jurisdictions before implementing any equity programme.

How do we effectively communicate equity value to employees?

Most employees struggle with equity concepts, making education crucial to build employee understanding and engagement.

Your communication should cover:

- Equity 101 education – what it is, how it works, explanations on key concepts like vesting, cliff periods, equity types, etc

- Equity philosophy – how equity fits into the company’s compensation philosophy

- Total compensation context – how equity fits within the overall rewards package

- What it means for employees – realistic value scenarios at different company valuations, and exercise mechanics detailing how employees can actually realise equity value in the future, with regular updates as the company grows.

Build an ongoing communication strategy with equity 101 sessions during onboarding covering basics and your specific programme, regular updates in company all-hands especially around funding rounds or valuation changes, equity discussions during performance reviews including any refresh grants, and clear exit guidance about exercise windows and decisions when employees leave.

Create written equity guides employees can reference, FAQ documents addressing common questions, examples and scenarios relevant to your company stage, and clear contact points for ongoing equity questions.