Implementing an effective management structure is crucial for efficient decision-making, strong communication, and productive teams.

But it isn’t easy to get right.

Hiring too many managers leads to a top heavy organisation structure – which means high payroll costs, difficulties getting alignment on priorities and decisions, and not enough individual contributors who are best-placed to deliver the hands-on work.

At the same time, too few managers stretched too thinly is also a problem, leaving teams lacking direction and support.

In this article we’ll take a look at Ravio’s data to understand what the optimal ratio of managers to employees looks like for a typical company, and we’ll share advice from expert People Leaders on how to design an optimal management structure for your company.

What makes an optimal management structure? Expert advice on common pitfalls

There are two main approaches to designing a management structure: hierarchical (centralised) or flat (decentralised).

Within the hierarchical approach, there are many different ways to implement, from functional to divisional to matrix to projectised hierarchies, and more.

The optimal management structure for an individual company depends on their business strategy, company culture, hiring plans, and more.

But there are common pitfalls amongst all approaches which can cause a suboptimal management structure – leading to inefficiencies, lack of alignment, poor decision-making, and low team productivity.

We asked three expert People Leaders for their top advice: JooBee Yeow, HR consultant and startup scaling specialist, Jessica During, founder of SmartScaling, and Andrew Duncan, Talent Director at Atomico. Here’s what they shared.

Tip 1: Map out the long-term organisation structure before hiring managers

Jessica During has extensive experience in recruitment and HR, both in-house for companies like Google, Expedia, and Enjoy Technology (where she grew the team from 10 to 350 people) and now as a consultant through her business Smart Scaling.

Jessica repeatedly sees startups making the same mistake with their management structure: failing to plan for the long-term.

“Startups can grow quickly,” Jessica says, “if you don’t think ahead to the teams and job levels you will have in the future, you might end up rapidly outgrowing your management structure.” Fixing a broken management structure is always going to be much more difficult than taking the time to implement one that can grow with you.

The right organisation structure varies from company to company, but one piece of advice from Jessica is to prioritise hiring department heads who have built successful teams before for companies with similar goals to yours.

“These individuals will bring with them insight on best practices. They’ll be able to guide on a well-planned hierarchy, and then they’ll take the lead on hiring additional managers for their department at the right times to lighten the workload as headcount increases.”

💡 Should we go for a flat organisation structure instead of a hierarchical one?

Andrew Duncan has supported countless startup founders with strategically designing and building leadership teams in both his previous role with The Up Group, and his current role as Talent Director at Atomico.

For Andrew, whilst many startups are opting for flat organisation structures today, this kind of management structure is “too often romanticised.”

In reality, “this only leads to a lack of accountability and a lack of leverage to drive functions forward towards business goals in an organised way. Once a company has a headcount of more than 20 people, a flat structure is simply ineffective.”

Subscribe to our newsletter for the monthly insights from Ravio's compensation dataset and network of Rewards experts 📩

Tip 2: Ensure alignment between business strategy and management structure

Following on from the importance of planning for the long-term, for Andrew Duncan, the most important factor in mapping out the management structure plan is to “have absolute clarity over the company’s overall goals and commercial objectives” and use this clarity to “design a management structure that aligns with the company’s trajectory and roadmap”.

In Andrew’s experience it’s common for companies to jump straight into hiring additional layers of management on an adhoc basis as the business grows and needs arise.

Over time this lack of alignment between business strategy and management structure can “result in a dysfunctional leadership team, because very little thought has gone into it.” But if management hiring is oriented around overall business goals, then “the team can be designed in a structured way with key functions built and managers hired as the company reaches key milestones.”

Andrew finds that bringing a great People Leader into a startup team early always help to bring this strategic thinking into hiring plans.

“When I moved to London from Silicon Valley seven years ago it was relatively rare for senior HR to be a priority hire in a European start up. The early people focus would centre on recruitment, with the rest left as an afterthought to figure out later. Fortunately, that’s changing today. And for good reason: strategic hiring and the health of the people function is absolutely crucial for overall business success.”

Tip 3: Prioritise diversity when hiring management teams

Inclusive leadership teams have been shown to make better business decisions up to 87% of the time, and yet we still see a startling lack of diversity in management.

“Diversity should always be part of that long-term planning for the management structure you want the company to have in the future” says Jessica, “both in terms of experience and leadership styles, as well as representation in terms of sex, race, sexuality, disabilities, and so on.”

For JooBee Yeow, diversifying experience levels is particularly important.

In JooBee’s experience as a Chief People Officer for several startups, and now an external consultant supporting scaling teams, it’s common for startups to want to fill new management positions with internal promotions of their best individual contributors.

“This leaves you with a management team that is entirely new to managing,” JooBee says, “and the transition from a specialist to a managerial role is the most profound shift in mindset in terms of one’s role and the definition of success – it isn’t just moving up a rung on the career ladder but a leap to an entirely different ladder!”

“Instead, hire experienced managers into the team to provide learning opportunities and guidance for inexperienced managers who have been promoted internally.”

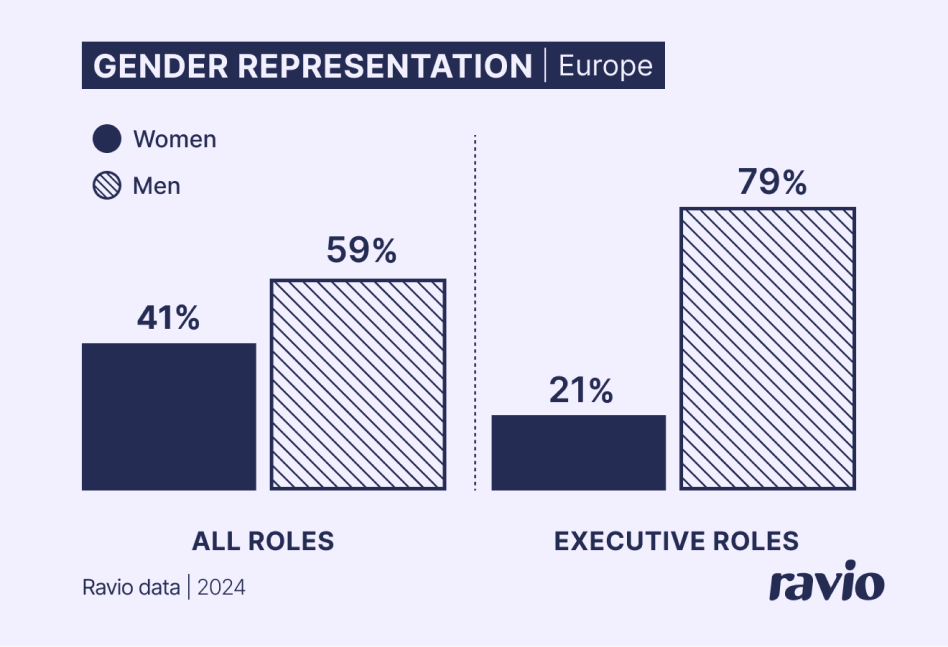

📊 Women are underrepresented in management roles, especially C-level

Data from Ravio’s pay equity software shows that female representation is lacking in the tech sector.

Men outnumber women in the tech industry, with only 41% of employees in Europe’s tech companies being women.

This gap widens as seniority increases: 36% of managers (M2) are women, 35% of senior managers (M3), 31% of directors (M4), and just 21% of executives.

Download our Pay Equity report to explore this lack of female leaders >

Tip 4: Ensure clarity on management vs IC career pathways before implementing the management structure

The tendency for startups to elevate top-performing individual contributors into managerial positions can also be problematic because it assumes that all top-performing employees will make successful managers, which isn’t always the case. Many individual contributors don’t enjoy the shift to management, and would have preferred a different career path.

JooBee Yeow’s advice is to “encourage ‘squiggly’ progression”. As we’ve seen, a linear path from individual contributor to manager to senior manager to director to VP is not right for all. With ‘squiggly’ progression, employees are able to make sideways moves to test out different functions or job roles, and progress in other ways. “It challenges the notion that progression equates to promotion into a manager position,” JooBee says, “growth in experience, knowledge, and skills can follow a non-linear path.”

To enable this culture, establishing a clear career track for individual contributors is a must. “Individual contributors often hit a ceiling in their ability to progress if they aren’t sure about managing,” JooBee says, “so ensure parallel career progression opportunities for employees who want to go down the manager route, and those that don’t, recognising the need for IC roles to lead increasingly complex projects or be involved in strategic initiatives.”

Tip 5: Implement a strong training plan for new managers

As we’ve seen, the jump from individual contributor to manager can be a tricky one for employees to navigate.

Many companies fail to provide support to facilitate the transition – research from the Center for Creative Leadership found that nearly 60% of managers received no training whatsoever when initially assuming a leadership role.

For JooBee, it’s vital to “clearly define the scope and expectations for each individual managerial role” to ensure an unbiased assessment of a candidate’s suitability for the role.

Once hired, both Jessica and Andrew emphasise the importance of providing a strong support plan for all new managers in the company – whether external hires or internal promotions.

“There has to be the right training opportunities and tools available for new managers to be effective leaders,” says Jessica, “without a training plan, you’re setting them up to fail.”

For Andrew, “a strong network for leadership advice” is also crucial. “At Atomico we always prioritise access to external mentors for leaders in our portfolio companies,” he says. “It’s also important that internal managers come from a mix of professional backgrounds – scrappy startups vs global corporations, for instance – to enable them to learn from one another too.”

Tip 6: Ensure a balanced ratio between managers and direct reports

Choosing the right cadence to hire management is key.

Hiring too many managers too quickly leaves you with a top heavy management structure and a narrow span of control per manager. This can damage the ability to make decisions and deliver. Plus, as Jessica highlights, “it can leave those employees unsatisfied with the scope of their role, which could impact your attrition rate.”

But, waiting too long to hire more managers can leave teams without direction and put huge amounts of pressure on the managers you do have, as they’re left with a wide span of control. “I’ve seen leaders with more than six direct reports burnout,” says Jessica, “and when that happens, the first thing to be sacrificed is managerial duties."

Jessica’s advice is to “view six direct reports as the ‘critical mass’ for your managers – if a manager has six direct reports, it’s time to review and plan the next steps in terms of management structures and hiring additional managers.”

How to tell if your management structure is too top heavy

The number of managers to direct reports is one of the most common issues in management structures – as Jessica During highlighted in the section above.

Key considerations include manager workload i.e. the amount of individual work to deliver that restricts time on direct reports, whether formalised processes are in place for regular tasks, and the experience of the direct reports i.e. how much support they will need from their manager.

However, the ‘right’ balance of employee to manager varies from company to company depending on company structure, size, culture, and so on.

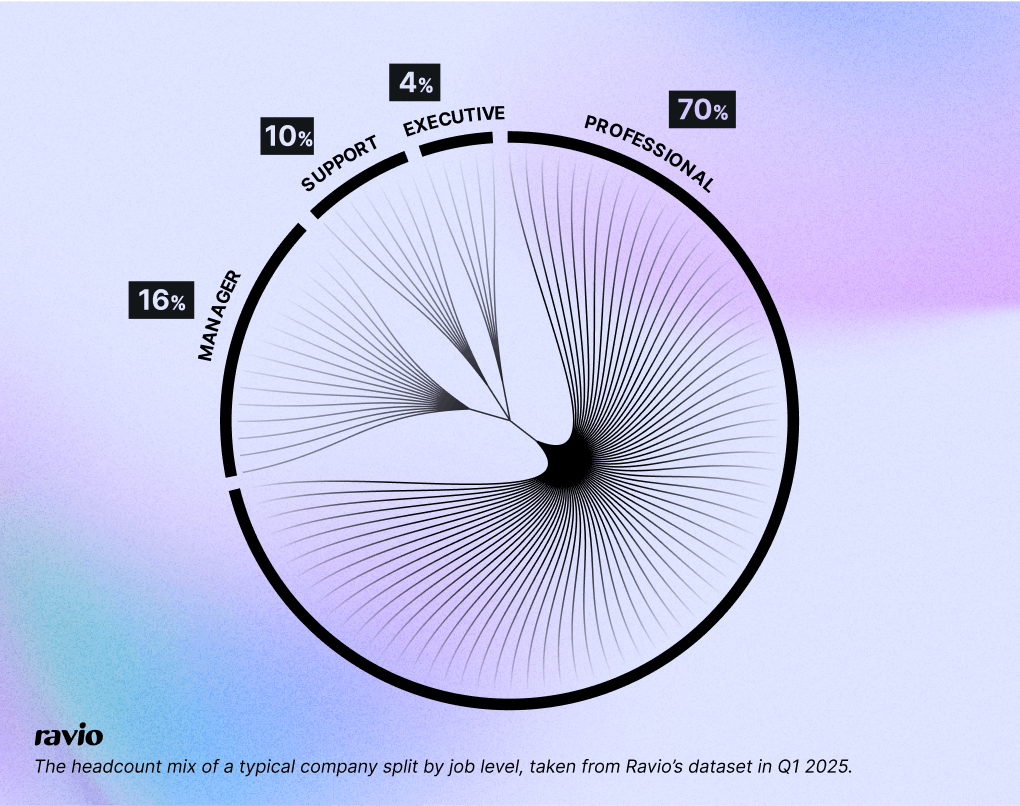

Let’s take a look at insights from Ravio’s compensation database on the typical manager to employee ratio.

How many direct reports is too many? The ideal manager to employee ratio

Earlier in this article, Jessica During advised that managers should have a maximum of six direct reports. Elsewhere, the ‘rule of seven’ is a common maxim in the business world, deeming that the effectiveness of managers diminishes if the number of people reporting to them exceeds seven.

This is surprisingly close to the reality for European tech companies.

Ravio’s data shows that average headcount mix for a company in the European tech industry includes:

- 16% managers

- 80% individual contributors (a combination of professional and support tracks)

This gives a ratio of around 1:5 – one manager for every five employees – which can be used to inform headcount planning.

Of course, it isn’t an exact science, so some managers will have more direct reports and some managers less.

There are also definitely exceptions to the rule that an ideal number of direct reports per manager is in the range of 5-7.

For instance, a very senior manager may have many more direct reports than this ideal number of 5-6, but those direct reports will also be fairly senior themselves and work largely autonomously – so there is less management time required.

Or, a manager in a call centre or customer service role might be responsible for dozens of team members, where the focus on supervision is very different to a people manager in other industries.

On the other hand, a manager might have fewer direct reports if those employees are very junior or are new to the industry or area of work and require much more time for supervision and training. Further, depending on the structure and lines of delegation, the manager may be required to also deliver work as an individual contributor, which reduces the time available for people management duties. In these cases, having 5-6 direct reports would be unmanageable.

"Alongside day to day activities you have projects. Alongside projects you have ‘emergencies’ that arise unexpectedly. Alongside these emergencies you’re also working on developing your direct reports: 1:1s, coaching sessions etc. Let’s not forget the ‘open door policy’ for wider team asks as needed. Oh and your ever-growing to do list of future work and projects too!"

Smart Scaling

How does management structure change as a company scales?

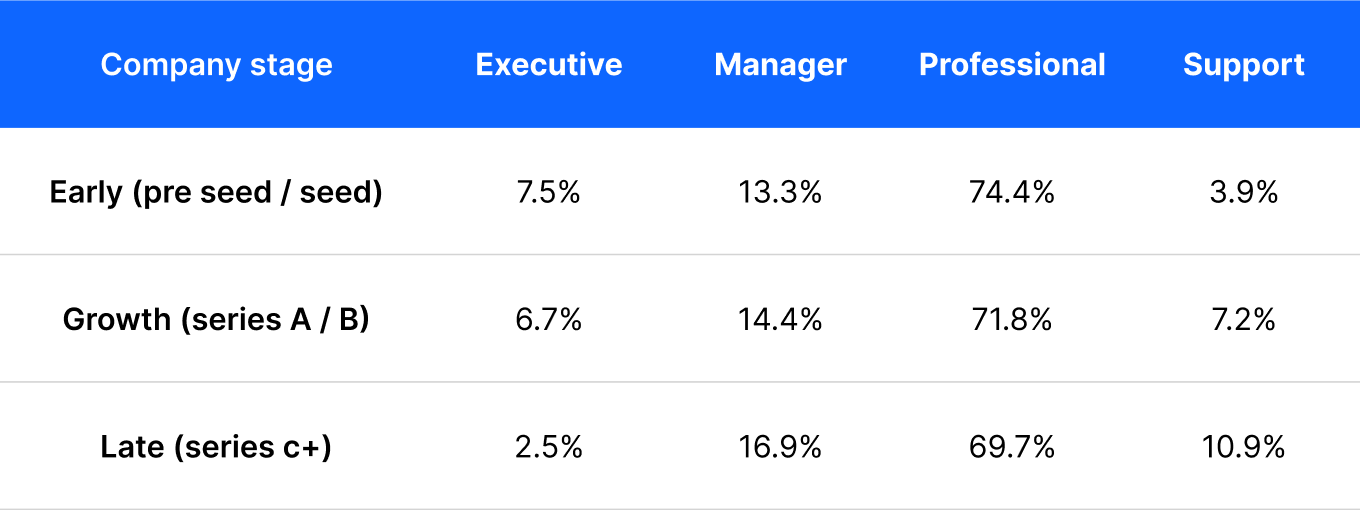

Ravio’s data shows variance in the ratio of managers to employees, depending on the stage of growth a company is at.

We can see that early-stage start ups have the highest proportion of executives and the lowest proportion of managers.

This makes sense given that there are less employees overall (e.g. in a 30 person team, 7% executives is just two people, which could even be two co-founders) and so there are less likely to be teams of people needing a manager at this stage – an early stage tech company, for instance, might have a couple of software engineering teams with a manager for each, but their marketing, operations, HR, and finance functions have only one or two employees each.

Notably, we can see there’s a substantial 2.5% increase in the proportion of management-level employees as companies move from growth to late-stage. New managers are being hired whilst the proportion of individual contributors remains exactly the same.

This tells us that there could be an inflection point as startups move from growth-stage to late-stage. This is when the number of management team members increases disproportionately to direct reports – so if you’re concerned about being a top heavy organisation, this is an important time to be aware of.

📊 Does the increase of managers in the late stage impact gender diversity?

There’s a lack of female representation in leadership roles in tech, with managers more likely to be men than women.

So it’s unsurprising that when the number of managers in an organisation increases, the gender pay gap also increases.

For instance, the gender pay gap in Fintech startups increases from 25% to 37% from growth-stage to late-stage – correlating with the stage at which the number of managers in the company increases too.

Given that both Jessica During and JooBee Yeow highlighted the importance of diversity in management structures earlier in this article, it’s important to keep an eye on this gender split when implementing management structures.

How to avoid a top heavy management structure

So how do you avoid a top heavy management structure?

As we’ve seen, the optimal ratio is around 5-7 direct reports per manager. If the average for your company is fewer direct reports than this then you have a top heavy organisation structure. If managers at your company have more direct reports than this then it’s time to consider bringing additional managers on board.

To avoid a top heavy organisation structure happening in the first place, it’s important keep an eye on the data so that you know when teams are off-balance with that ideal manager to employee ratio.

Plus, as our experts highlighted earlier in this article, plan the ideal long-term organisational structure (aligned with overall business strategy) first, to ensure that every new manager hired is a strategic hire that will move the business forward towards its goals.

💡 Use Ravio to analyse your organisation structure

Ravio’s compensation management software enables you to analyse your workforce, including visualising whether your company may be top heavy.

Plus, see internal data against external market benchmarks to see how your headcount and management structure compares to other companies in your market.